IT’S ABOUT ART, MUSIC & LITERATURE

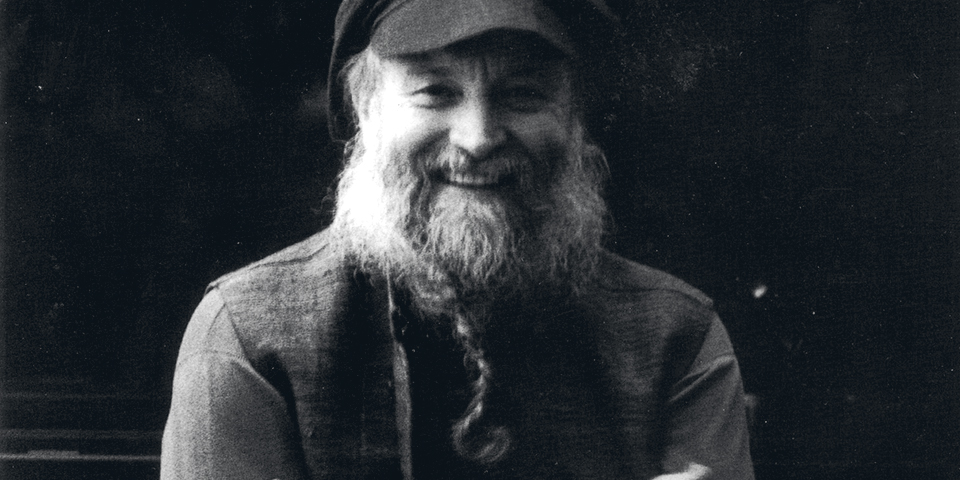

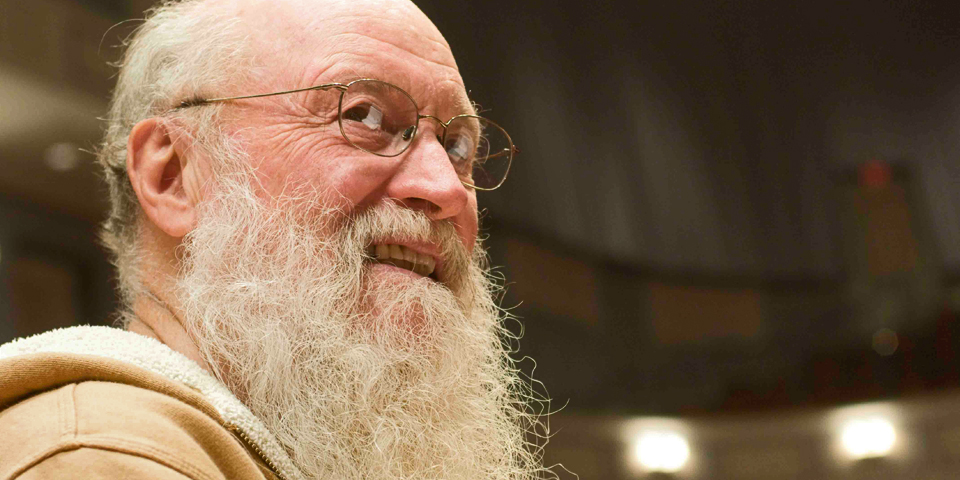

TERRY RILEY

THE MINIMALIST MOVEMENT

Ambient music has been around for centuries, take the call of Whales, or the drone of a dijereedoo, it’s only recently in the 70’s that “ambient” has been used as a term to classify music. Brian Eno was, in the main, responsible for this, with his concept of threshold hearing. Eno was very influenced by a generation of composers whose work came to prominence in the sixties — the minimalists, central of whom is the california based composer Terry Riley.

It Seems Like We Are Moving Towards Something

“The incredible thing about the human mind is that is didn’t come with an instruction book.”

A Rainbow in Curved Air 1969

Persian Surgery Dervishes 1972

Rare Footage — Live In The 1970s

Live in Grass Valley, CA 2010

California Composer Terry Riley launched what is now known as the Minimalist movement with his revolutionary classic IN C in 1964. This seminal work Provided a new concept in musical form based on interlocking repetitive patterns. It’s impact was to change the course of twentieth–century music and it’s influence has been heard in the works of prominent composers such as Steve Reich, Philip Glass and John Adams and in the music of Rock Groups such as The Who, The Soft Machine, Tangerine Dream, Curved Air and many others. Terry’s hypnotic, multi–layered, polymetric, brightly orchestrated eastern flavored improvisations and compositions set the stage for the prevailing interest in a new tonality.

While working on a masters degree at UC Berkeley in 1960, he met La Monte Young, whose radical approach to time made a big impact and the two made a life long association.

During this time Riley and Young worked out many of their seminal ideas while working with influential dancer Anna Halprin.

During a sojourn to Europe 1962–64 he collaborated with members of the Fluxus group, playwright Ken Dewey and trumpeter Chet Baker and was involved in street theater and happenings.

In 1965 he move to New York and joined La Monte Young’s Theater of Eternal Music.

1967 was the year of his first all night concert at the Philadelphia College of Art and he began a collaboration with art artist Robert Benson resulting in more all night concerts.

Recordings of In C, A Rainbow in Curved Air, Poppy Nogood and the Phantom Band and the Church of Anthrax were all issued by CBS Masterworks in 1968–69.

In 1970, Terry became a disciple of the revered North Indian Raga Vocalist, Pandit Pran Nath and made the first of his numerous trips to India to study with the Master. He appeared frequently in concert with the legendary singer as tampura, tabla and vocal accompanist over the next 26 years until Pran Naths passing in 1996. He has co–directed along with Sufi Murshid, Shabda Kahn of the Chisti Sabri India music study tours 1993–2000.

Terry regularly appears in concerts of Indian Classical Music and conducts raga singing seminars.

While teaching at Mills College in Oakland in the 1970’s he met David Harrington, founder and leader of the Kronos Quartet and began the long association that has so far produced 13 string quartets, a quintet, Crows Rosary and a concerto for string quartet, The Sands [1990], which was the Salzburg Festival’s first new music commission and SUN RINGS [2003], the 2 hour multi media piece for choir, arts and Space sounds, commissioned by NASA.

The Cusp of Magic [2004] another quintet for Kronos features Wu Man, pipa, and was released on Nonesuch records in 2007.

Cadenza on the Night Plain was selected by both Time and Newsweek as one of the 10 best Classical albums of the year.

The epic 5 quartet cycle, Salome Dances for Peace was selected as the #1 Classical album album of the year by USA Today and was nominated for a Grammy.

The orchestral piece Jade Palace was commissioned by Carnegie Hall for the Centennial celebration 1990/91. It was premiered there by Leonard Slatkin and the Saint Louis Symphony.

June Buddha’s, for Chorus and Orchestra, based on Jack Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues was commissioned by the Koussevitsky foundation in 1991.

Interviewer

Basically tell us who you are.

Terry Riley

Well I guess my music came to prominence around one piece called In C which I wrote in 1964 at that time it was called The Global Villages for Symphonic Pieces, because it was a piece built out of fifty three simple patterns and the structure was new to music at that time. No one had done anything like this before were you just had a piece built all out of patterns and the first concerts of In C were kind of big communal events where a lot of people would come out and sometimes listen or dance to the music because the music would get quite ecstatic with all these repeated patterns. Although repetition is a major force in music it was never used in this way before. So, essentially my contribution was to introduce repetition into Western music as the main ingredient without any melody over it, without anything just repeated patterns, musical patterns. In the nut shell that was my own introduction into the world of western music.

Interviewer

What were you doing before In C came out?

Riley

I was working with Anna Halprins Dance Company. I was working with tape loops, sort of primitive technology. This was in the late fifties early sixties. I was using tape loops for dancers and dance production. I had very funky primitive equipment, in fact technology wasn’t very good no matter how much money you had. Everything was mono. Using these machines I would take tapes and run them into my yard and around a wine bottle back into my room and I would get a really long loop and then I would cut the tape into all different sizes and I would just run them out into the yard and I would record onto one machine just sound on sound. I would build up this kind of unintelligible layer, almost like some of these things you have been playing. It was like primitive sampling. I would take things like Junior Walker and his All Stars and would cut it up and play it backwards and stuff like that. Out of doing all that experimentation with sound I decided I wanted to do it with live musicians. To take repetition, take music fragments and make it live. Musicians would be able to play it and create this kind of abstract fabric of sound.

Interviewer

What kind of instruments were you playing at this time?

Riley

I was mainly playing piano.

Interviewer

Your first record was called Reed Stream.

Riley

That was on an old organ harmonium that I had a vacuum cleaner motor blower blowing into the ballast’s. The vacuum cleaner motor kind of had a drone, so I played along with that. Talking about the all night concerts, I did some of the first all night concerts back in the sixties with this little harmonium, and I also had saxophone taped delays. I was asked to do the first all night concerts. I did a solo all night concert which started at 10:00 at night and ended at sunrise. People brought their whole families and they had their sleeping bags and hammocks. It was in one of the big rooms in art college. It started out a career for me doing all night concerts which I did for a couple of years.

Interviewer

How did you prepare for these all night concerts?

Riley

I really didn’t have a plan, I just went in and started playing. one of my specialties was to be able to play for a really long time without stopping and I would play these repeated patterns for hours and hours and I wouldn’t seem to get tired. I guess I have a lot of energy. Throughout the evening I would be recording these long saxophone delays and about four hours into the concert, if I wanted to take a break I would just play back the saxophone. And a lot of people didn’t even wake up to know the difference because a lot of people just slept all night.

Interviewer

I heard in a lot of your concerts you used lights shows?

Riley

I traveled with an artist, Bob Benson, he used have strobe lights and we built these mylar screens. He was a painter essentially. His paintings were stretch color fabric on canvas, then he started stretching reflective mylar. Sometimes I would have troops of girl gymnasts doing cartwheels during the night shows just as a passing. Then we would have these mylar things so the audience would see themselves and they would see me. They looked quite distorted because the mylar, as it bends, distorts the reflection kind of like the mirrors at the circus.

Interviewer

When people talk about minimalist music the lineage seems to go [according to media] La monte Young, you, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and I was wondering when you first came across La monte what went on between you. I know you’ve played concerts together, I always got the impression that the influence went both ways.

Riley

Well, he was certainly a big influence on me when I met him, he was the freakiest guy I have ever met in my life. I met him when I went to school in Berkeley. He was in one of my classes and we struck it off as close friends from the beginning. I think he was much more sophisticated musician. He had lived in Los Angeles and been a jazz musician, and I was coming out of the sticks of Northern California and I hadn’t heard nearly as much music as he had. He has a superb conceptual sense about music, I think his sense about music is what spawned minimalist music, even though he didn’t do it the way Glass and Reich, who where more inspired by me because of the repetition. La monte’s idea was just to have this one big form that were just long tones, I think that was the real essential heart of minimalist music.

Interviewer

How were those pieces live?

Riley

He wrote one for me, that I’ve never performed yet, but maybe I will someday. It was where I was supposed to push a grand piano into a wall and keep pushing until the wall fell down.

Interviewer

Could you talk a little about your encounters and development of your relationship with Pandit Pran Nath?

Riley

I met him through La monte Young. La monte had brought him over in 1970 and La monte had been one of the first people in America to recognize how great he was. He had been underground figure performing in India on the radio. He wasn’t considered by the Indian public at large as one of the great superstars, like Ravi Shankar. But in effect, he had all this great knowledge of Indian classical music and really performed it in a true sense. I had been interested in Indian music and I actually started studying Tableaus before I met him. I was sort of going in that direction because my own music was very similar to Indian music. When I met him [Guruji] he said “You must become my student”. So I said, “OK”. I cried the first time I heard him sing. He hit some bell in me that had never resonated before. It was so moving I wanted to go back to India with him right away and start studying with him. I had already done Rainbow in Curved Air and had a big record on CBS. I was launched to have a long career and then I just dropped out and went to India. So I just went to India to study with Pandit, and he said no you have to do your own music too.

Interviewer

Tell us about the music–theater piece you are working on now?

Riley

It is based on the works of Adolph Wulfi. He was a Swiss peasant who was born around 1864 and had a terrible childhood. He was neglected, his father was an alcoholic, he was a ward of the state, his mother died when he was very young and he was sent out as a hireling around the farms in Switzerland. He wandered around Switzerland like this for about thirty years as a laborer and stuff. Around the age of thirty he was caught molesting a young child in a cradle. He actually had been involved in other cases before too and had been put in jail because of one of them. But when he was thirty, they had diagnosed him as schizophrenic and was put in a mental institution, and spent the next thirty–five years almost in solitary confinement. In this mental institution and after about five years he started drawing and he had the most incredible ability to draw and conceptualize art considering he had never been to art school and knew nothing about what was happening. He was a very visionary artist. His art is always about vision of something. One of his hallucinations or he said people would visit him and tell him what to draw and then they would argue about what he should draw and then he would argue with them. But he turned out thirty thousand or something drawings and stories about travels through space, travels throughout the earth, places he had never been too, because he spent his entire life in a mental institution. He described New York and Canada in great detail and gave them really fantastic names, with great plays on words. When I first discovered his art, it was like a revelation. I had never heard of him, I couldn’t believe it, he was such a great artist and nobody never heard about him. But now outsider art is beginning to get known. After I saw Wulfi’s work, I wanted to do some piece on him because he really set off something in me when I saw it, I felt like I had to deal with it. First I was going to make it purely a musical piece and then it looked like it had to be a theater piece because a lot of Wulfie’s writings are so imaginative and his words are so imaginative, I thought they had to be spoken in each piece so we sort of developed this woven fabric of music and narrative dialog. We would mix it all together with video images and slides. Then the actors were speaking and telling stories.

Interviewer

Are the words sung or spoken?

Riley

Some of them are spoken and I’ve written some songs for the scripts. Some of them are in German and others are in English. Some of the ones in German are just based on sounds which are really interesting, there even not sounds common to Germany. They are sounds Wulfli had made up. You know there is this language schizophrenics call Glosserlallia which is a secret language that only they understand.

Interviewer

So schizophrenics can talk to each other in this language?

Riley

No, they can only talk to themselves. Most of them have many people dwelling within themselves, and they all speak Glosserlallia. They probably each have their own version of the language. I found that to be fascinating though. The big part of art and music is imagination. The thing that grips us is imagination of the artist, and schizophrenics are some of the most imaginative people. It makes you wonder what is the real heart of art and music. What are we really trying to get at? I think what happens to them, their ordinary filters for reality somehow open up. They experience things we can only experience in very altered states, but they experience this all the time.

Interviewer

Did you see music in Wulfli’s pictures, and did you develop themes to certain pictures?

Riley

I did. A lot of his drawings also have music notations in them. He developed his own system of music notation and no one has ever been able to decipher it. It is very cryptic and enigmatic notation. When I saw a lot of those I really thought it sounded like great music just looking at it on the page although I would never know how to decipher it, so I decided to compose music just in a spirit of what he is doing. I wanted to write music that was influenced by my studying his drawings. So I spent a lot time this summer just gazing at the drawings. The music has come out kind of interesting, it almost sounds like music that could have been composed in the 30’s and 40’s around the time he lived. I haven’t really wanted to do anything modern. It’s general substance is older sounding.

Interviewer

What are your thoughts on where the world is going?

Riley

It is important that we are coming up on the millennium because what I am experiencing, just being one person out of billions, is the feeling of acceleration. I experience this through my contact with other people. Everyone seems to be in a kind of accelerated time mode that is beyond their own control. Acceleration is finite, I think according to some laws of physics. It seems like we are moving towards something, some kind of point and it is probably going to be an important point in our development or dissolution. That is what everybody seems to be thinking. We are either going to dissolve as a human race or we are going to break through into a new understanding of what it is to be a human being.

Interviewer

So what part is music going to take in this transformation?

Riley

This morning I was practicing raga, and at one point I was singing a long tone and I became very peaceful and still. I thought this is really the highest point of music for me is to become in a place where there is no desire, no craving, wanting to do anything else, just to be in a state of being to the highest point. Then you get a little meditated, you get to a place that is really still and it is the best place you have ever been and yet there is nothing there. For me, that is what music is. It is a spiritual art. It is a form to that place. There are many ways to do that, many kind of ways to get there. Music can also be a sensual pleasure, like eating food or sex. But its highest vibration for me is that point of taking us to a real understanding of something in our nature which we can very rarely get at. It is a spiritual state of oneness. For me, it is the reason for doing music because you are always trying to get there, but we live in this big cloud of illusions, so we sometimes go about it in the wrong way. We think music as being as a highly skilled activity, virtuosity. To me it’s important that you acheive the state. Listening to music is as high as singing or playing it. If a great singer is singing and you think gee I would like to sing like that, you are being foolish because you are listening to the thing you really want anyway, so why think you want to do it. It is the thing, the thing itself that is really important. Although I have a personal greed about playing music, I really enjoy the tactile thing of playing an instrument, but I’m coming from back in 1935, when that was the way you made music, there is no other way to do it, so I have a lifelong habit of doing music this way. But if I was 20 years old today, I might not have that orientation, I would probably be out sampling music like everybody else.