IT’S ABOUT ART, MUSIC & LITERATURE

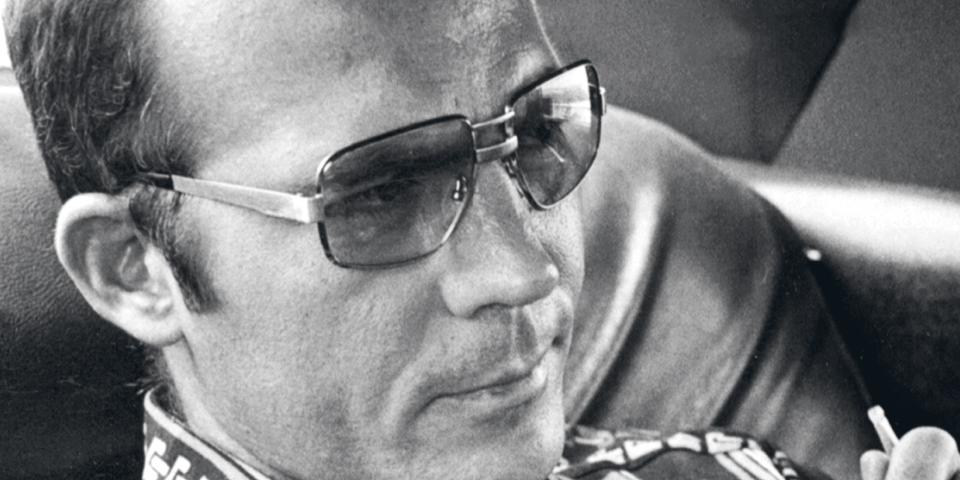

HUNTER S. THOMPSON

THE ART OF GONZO–JOURNALISM

In an October 1957 letter to a friend who had recommended he read Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, Hunter S. Thompson wrote: Although I don’t feel that it’s at all necessary to tell you how I feel about the principle of individuality, I know that I’m going to have to spend the rest of my life expressing it one way or another, and I think that I’ll accomplish more by expressing it on the keys of a typewriter than by letting it express itself in sudden outbursts of frustrated violence …

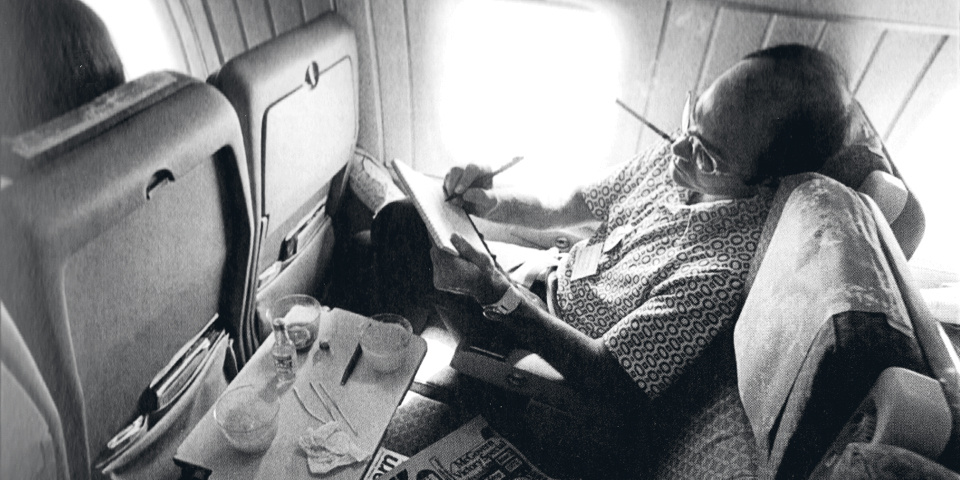

Hunter S. Thompson Omnibus 1978

“Crazy is a term of art Insane is a term of law. Remember that, and you will save yourself a lot of trouble.”

Hunter S. Thompson Meets A Hell’s Angel 1967

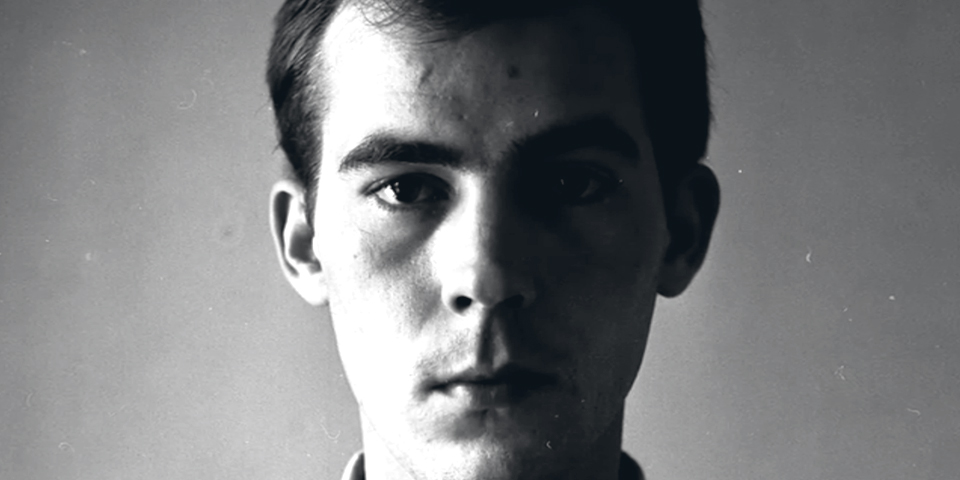

The Proud Highway

Thompson carved out his niche early. He was born in 1937, in Louisville, Kentucky, where his fiction and poetry earned him induction into the local Athenaeum Literary Association while he was still in high school. Thompson continued his literary pursuits in the United States Air Force, writing a weekly sports column for the base newspaper. After two years of service, Thompson endured a series of newspaper jobs — all of which ended badly — before he took to freelancing from Puerto Rico and South America for a variety of publications. The vocation quickly developed into a compulsion.

Thompson completed The Rum Diary, his only novel to date, before he turned twenty — five, bought by Ballantine Books, it finally was published — to glowing reviews — in 1998. In 1967, Thompson published his first nonfiction book, Hell’s Angels, a harsh and incisive firsthand investigation into the infamous motorcycle gang then making the heartland of America nervous.

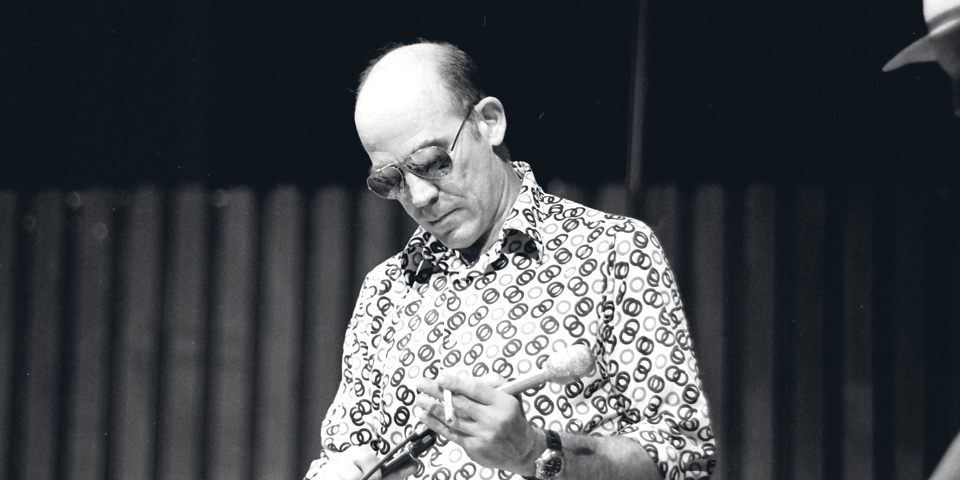

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which first appeared in Rolling Stone in November 1971, sealed Thompson’s reputation as an outlandish stylist successfully straddling the line between journalism and fiction writing. As the subtitle warns, the book tells of a savage journey to the heart of the American Dream in full — tilt gonzo style — Thompson’s hilarious first — person approach — and is accented by British illustrator Ralph Steadman’s appropriate drawings.

His next book, Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72, was a brutally perceptive take on the 1972 Nixon — McGovern presidential campaign. A self–confessed political junkie, Thompson chronicled the 1992 presidential campaign in Better than Sex [1994]. Thompson’s other books include The Curse of Lono [1983], a bizarre South Seas tale, and three collections of Gonzo Papers: The Great Shark Hunt [1979], Generation of Swine [1988] and Songs of the Doomed [1990].

In 1997, The Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, 1955–1967, the first volume of Thompson’s correspondence with everyone from his mother to Lyndon Johnson, was published. The second volume of letters, Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist, 1968–1976, has just been released.

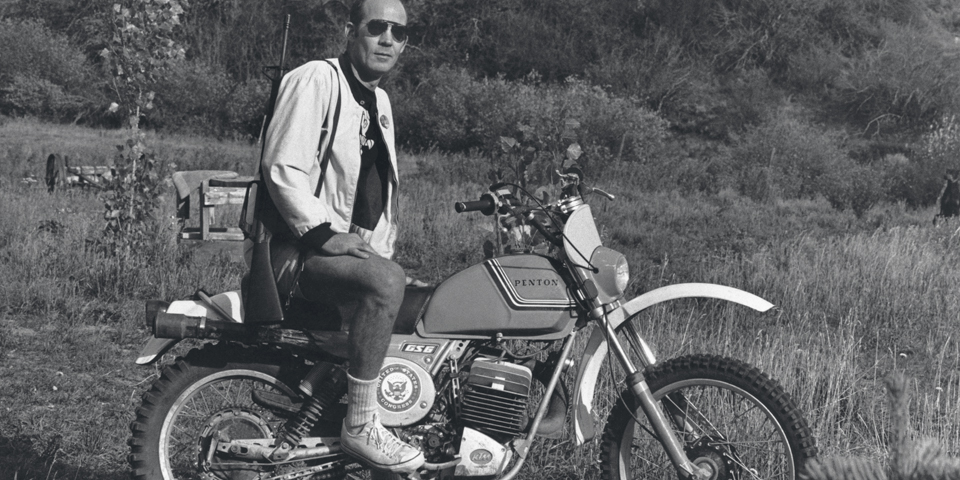

Located in the mostly posh neighborhood of western Colorado’s Woody Creek Canyon, ten miles or so down — valley from Aspen, Owl Farm is a rustic ranch with an old — fashioned Wild West charm. Although Thompson’s beloved peacocks roam his property freely, it’s the flowers blooming around the ranch house that provide an unexpected high — country tranquility. Jimmy Carter, George McGovern and Keith Richards, among dozens of others, have shot clay pigeons and stationary targets on the property, which is a designated Rod and Gun Club and shares a border with the White River National Forest. Almost daily, Thompson leaves Owl Farm in either his Great Red Shark Convertible or Jeep Grand Cherokee to mingle at the nearby Woody Creek Tavern.

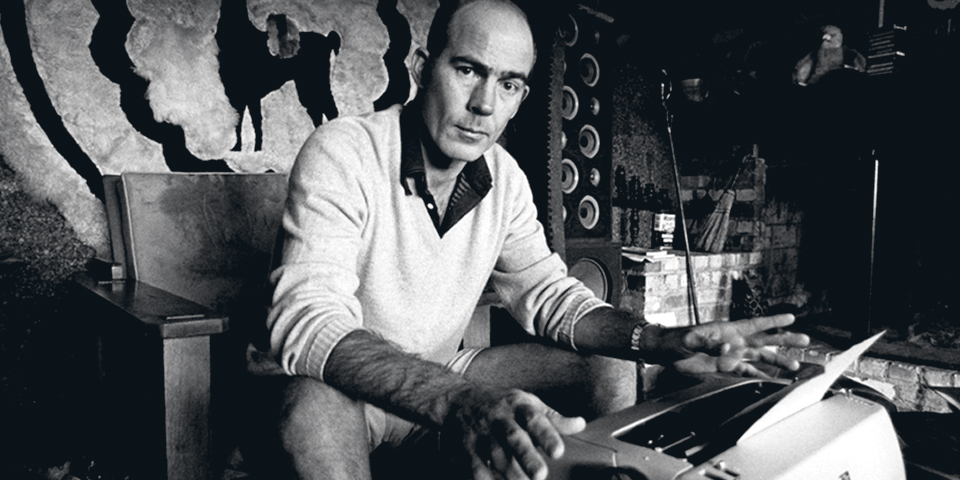

Visitors to Thompson’s house are greeted by a variety of sculptures, weapons, boxes of books and a bicycle before entering the nerve center of Owl Farm, Thompson’s obvious command post on the kitchen side of a peninsula counter that separates him from a lounge area dominated by an always — on Panasonic TV, always tuned to news or sports. An antique upright piano is piled high and deep enough with books to engulf any reader for a decade. Above the piano hangs a large Ralph Steadman portrait of Belinda — the Slut Goddess of Polo. On another wall covered with political buttons hangs a Che Guevara banner acquired on Thompson’s last tour of Cuba. On the counter sits an IBM Selectric typewriter — a Macintosh computer is set up in an office in the back wing of the house.

The most striking thing about Thompson’s house is that it isn’t the weirdness one notices first: it’s the words. They’re everywhere — handwritten in his elegant lettering, mostly in fading red Sharpie on the blizzard of bits of paper festooning every wall and surface: stuck to the sleek black leather refrigerator, taped to the giant TV, tacked up on the lampshades, inscribed by others on framed photos with lines like, For Hunter, who saw not only fear and loathing, but hope and joy in ’72 — George McGovern, typed in IBM Selectric on reams of originals and copies in fat manila folders that slide in piles off every counter and table top, and noted in many hands and inks across the endless flurry of pages.

Thompson extricates his large frame from his ergonomically correct office chair facing the TV and lumbers over graciously to administer a hearty handshake or kiss to each caller according to gender, all with an easy effortlessness and unexpectedly old — world way that somehow underscores just who is in charge.

We talked with Thompson for twelve hours straight. This was nothing out of the ordinary for the host: Owl Farm operates like an eighteenth — century salon, where people from all walks of life congregate in the wee hours for free exchanges about everything from theoretical physics to local water rights, depending on who’s there. Walter Isaacson, managing editor of Time, was present during parts of this interview, as were a steady stream of friends. Given the very late hours Thompson keeps, it is fitting that the most prominently posted quote in the room, in Thompson’s hand, twists the last line of Dylan Thomas’s poem Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night: Rage, rage against the coming of the light.

For most of the half — day that we talked, Thompson sat at his command post, chain — smoking red Dunhills through a German — made gold — tipped cigarette filter and rocking back and forth in his swivel chair. Behind Thompson’s sui generis personality lurks a trenchant humorist with a sharp moral sensibility. His exaggerated style may defy easy categorization, but his career — long autopsy on the death of the American dream places him among the twentieth–century’s most exciting writers. The comic savagery of his best work will continue to electrify readers for generations to come.

I have stolen more quotes and thoughts and purely elegant little starbursts of writing from the Book of Revelation than from anything else in the English Language — and it is not because I am a biblical scholar, or because of any religious faith, but because I love the wild power of the language and the purity of the madness that governs it and makes it music.

Hunter S. Thompson

Well, wanting to and having to are two different things. Originally I hadn’t thought about writing as a solution to my problems. But I had a good grounding in literature in high school. We’d cut school and go down to a café on Bardstown Road where we would drink beer and read and discuss Plato’s parable of the cave. We had a literary society in town, the Athenaeum, we met in coat and tie on Saturday nights. I hadn’t adjusted too well to society — I was in jail for the night of my high school graduation — but I learned at the age of fifteen that to get by you had to find the one thing you can do better than anybody else … at least this was so in my case. I figured that out early. It was writing. It was the rock in my sock. Easier than algebra. It was always work, but it was always worthwhile work. I was fascinated early by seeing my byline in print. It was a rush. Still is.

When I got to the Air Force, writing got me out of trouble. I was assigned to pilot training at Eglin Air Force Base near Pensacola in northwest Florida, but I was shifted to electronics … advanced, very intense, eight — month school with bright guys … I enjoyed it but I wanted to get back to pilot training. Besides, I’m afraid of electricity. So I went up there to the base education office one day and signed up for some classes at Florida State. I got along well with a guy named Ed and I asked him about literary possibilities. He asked me if I knew anything about sports, and I said that I had been the editor of my high — school paper. He said, Well, we might be in luck. It turned out that the sports editor of the base newspaper, a staff sergeant, had been arrested in Pensacola and put in jail for public drunkenness, pissing against the side of a building, it was the third time and they wouldn’t let him out.

So I went to the base library and found three books on journalism. I stayed there reading them until it closed. Basic journalism. I learned about headlines, leads: who, when, what, where, that sort of thing. I barely slept that night. This was my ticket to ride, my ticket to get out of that damn place. So I started as an editor. Boy, what a joy. I wrote long Grantland Rice — type stories. The sports editor of my hometown Louisville Courier Journal always had a column, left — hand side of the page. So I started a column.

By the second week I had the whole thing down. I could work at night. I wore civilian clothes, worked off base, had no hours, but I worked constantly. I wrote not only for the base paper, The Command Courier, but also the local paper, The Playground News. I’d put things in the local paper that I couldn’t put in the base paper. Really inflammatory shit. I wrote for a professional wrestling newsletter. The Air Force got very angry about it. I was constantly doing things that violated regulations. I wrote a critical column about how Arthur Godfrey, who’d been invited to the base to be the master of ceremonies at a firepower demonstration, had been busted for shooting animals from the air in Alaska. The base commander told me: Goddamn it, son, why did you have to write about Arthur Godfrey that way?

When I left the Air Force I knew I could get by as a journalist. So I went to apply for a job at Sports Illustrated. I had my clippings, my bylines, and I thought that was magic … my passport. The personnel director just laughed at me. I said, Wait a minute. I’ve been sports editor for two papers. He told me that their writers were judged not by the work they’d done, but where they’d done it. He said, Our writers are all Pulitzer Prize winners from The New York Times. This is a helluva place for you to start. Go out into the boondocks and improve yourself.

I was shocked. After all, I’d broken the Bart Starr story.

Interviewer

What was that?

Hunter S. Thompson

At Eglin Air Force Base we always had these great football teams. The Eagles. Championship teams. We could beat up on the University of Virginia. Our bird — colonel Sparks wasn’t just any yo — yo coach. We recruited. We had these great players serving their military time in ROTC. We had Zeke Bratkowski, the Green Bay quarterback. We had Max McGee of the Packers. Violent, wild, wonderful drunk. At the start of the season McGee went AWOL, appeared at the Green Bay camp and he never came back. I was somehow blamed for his leaving. The sun fell out of the firmament. Then the word came that we were getting Bart Starr, the All — American from Alabama. The Eagles were going to roll! But then the staff sergeant across the street came in and said, I’ve got a terrible story for you. Bart Starr’s not coming. I managed to break into an office and get out his files. I printed the order that showed he was being discharged medically. Very serious leak.

Interviewer

The Bart Starr story was not enough to impress Sports Illustrated?

Hunter S. Thompson

The personnel guy there said, Well, we do have this trainee program. So I became a kind of copy boy.

Interviewer

You eventually ended up in San Francisco. With the publication in 1967 of Hell’s Angels, your life must have taken an upward spin.

Hunter S. Thompson

All of a sudden I had a book out. At the time I was twenty — nine years old and I couldn’t even get a job driving a cab in San Francisco, much less writing. Sure, I had written important articles for The Nation and The Observer, but only a few good journalists really knew my byline. The book enabled me to buy a brand new BSA 650 Lightning, the fastest motorcycle ever tested by Hot Rod magazine. It validated everything I had been working toward. If Hell’s Angels hadn’t happened I never would have been able to write Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas or anything else. To be able to earn a living as a freelance writer in this country is damned hard, there are very few people who can do that. Hell’s Angels all of a sudden proved to me that, Holy Jesus, maybe I can do this. I knew I was a good journalist. I knew I was a good writer, but I felt like I got through a door just as it was closing.

Interviewer

With the swell of creative energy flowing throughout the San Francisco scene at the time, did you interact with or were you influenced by any other writers?

Hunter S. Thompson

Ken Kesey for one. His novels One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion had quite an impact on me. I looked up to him hugely. One day I went down to the television station to do a roundtable show with other writers, like Kay Boyle, and Kesey was there. Afterwards we went across the street to a local tavern and had several beers together. I told him about the Angels, who I planned to meet later that day, and I said, Well, why don’t you come along? He said, Whoa, I’d like to meet these guys. Then I got second thoughts, because it’s never a good idea to take strangers along to meet the Angels. But I figured that this was Ken Kesey, so I’d try. By the end of the night Kesey had invited them all down to La Honda, his woodsy retreat outside of San Francisco. It was a time of extreme turbulence — riots in Berkeley. He was always under assault by the police — day in and day out, so La Honda was like a war zone. But he had a lot of the literary, intellectual crowd down there, Stanford people also, visiting editors, and Hell’s Angels. Kesey’s place was a real cultural vortex.

Interviewer

Did you ever entertain the idea of writing a novel about the whole Bay area during this period, the sixties, in the vein of Tom Wolfe’s Electric Acid Kool — Aid Test?

Hunter S. Thompson

Well, I had thought about writing it up. It was obvious to me at the time that the Kesey action was on a continuum with the Hell’s Angels book. It seemed to me for a while that I should write a book, probably the same one that Wolfe wrote, but at the time I wasn’t really into it. I couldn’t do another piece of journalism.

Interviewer

Did you connect at all with Tom Wolfe during the San Francisco heyday?

Hunter S. Thompson

It’s interesting. I wanted to review Wolfe’s book, The Kandy — Kolored Tangerine — Flake Streamline Baby. I’d read some of it in Esquire, got a copy, had a look at it and was very, very impressed. The National Observer had taken me off politics by then, so book reviews were about the only thing I could do that they didn’t think controversial. I had wanted to cover Berkeley and acid, and all that, but they didn’t want any of it. So I picked up Wolfe’s book and wrote a glowing review and sent it in to the Observer, and my editor, Clifford Ridley, was pleased with it. About a week went by and I hadn’t heard anything. Then my editor called me up and said, We’re not going to run the review. It was the first one they ever said no to, up until that point my reviews had been full — page lead pieces, like in the Times Book Review, and I was shocked that they would turn it down. I asked, Why are you turning it down? What’s wrong with you? The guy obviously felt guilty, so he let me know there was an editor at the Observer who had worked with Wolfe somewhere else and didn’t like him, so he had killed my review. So I took the review and sent it to Tom Wolfe with a letter saying, the Observer won’t run this because somebody there has a grudge against you, but I wanted you to get it anyway since I worked real hard on it, and your book was brilliant. I thought you should have it even though they won’t print it. Then I took my carbons of that letter and sent them to the Observer. They said I’d been disloyal. That’s when I was terminated. I just felt it was important not only that Wolfe knew about it, but that the Observer editors knew that I had turned them in. It sounds kind of perverse, but I’d do it again. But that’s how Tom and I got to know each other. He would call me for directions or advice when he was working on the Acid book.

Interviewer

Did that friendship and Wolfe’s journalism have much of an impact on your writing?

Hunter S. Thompson

Wolfe proved that you could kind of get away with it. I saw myself as having a tendency to cut loose — like Kesey — and Wolfe seemed to embrace that as well. We were a new kind of writer, so I felt it was like a gang. We were each doing different things, but it was a natural kind of hook — up.

Interviewer

Wolfe later included you in his book, The New Journalism.

Hunter S. Thompson

I was the only one with two entries, in fact. He appreciated my writing and I appreciated his.

Interviewer

As you explored the acid scene did you ever develop a feel for Timothy Leary?

Hunter S. Thompson

I knew the bastard quite well. I ran into him a lot in those days. As a matter of fact I got a postcard invitation from something called the Futique Trust in Aptos, California, inviting me to attend the fourth annual Timothy Leary Memorial Celebration and Potluck Picnic. The invitation was printed in happy letters, with a peace symbol in the background, and I felt a burst of hate in my heart when I saw it. Every time I think about Tim Leary I get angry. He was a liar and a quack and a worse human being than Richard Nixon. For the last twenty — six years of his life he worked as an informant for the FBI and turned his friends into the police and betrayed the peace symbol he hid behind.

Interviewer

The San Francisco scene brought together many unlikely pairs — you and Allen Ginsberg, for instance. How did you come to know Allen during this period?

Hunter S. Thompson

I met Allen in San Francisco when I went to see a marijuana dealer who sold by the lid. I remember it was ten dollars when I started going to that apartment and then it was up to fifteen. I ended up going there pretty often, and Ginsberg — this was in Haight — Ashbury — was always there looking for weed too. I went over and introduced myself and we ended up talking a lot. I told him about the book I was writing and asked if he would help with it. He helped me with it for several months, that’s how he got to know the Hell’s Angels. We would also go down to Kesey’s in La Honda together. One Saturday, I drove down the coast highway from San Francisco to La Honda and I took Juan, my two — year — old son, with me. There was this magnificant crossbreeding of people there. Allen was there, the Hell’s Angels — and the cops were there too, to prevent a Hell’s Angels riot. Seven or eight cop cars. Kesey’s house was across the creek from the road, sort of a two — lane blacktop country compound, which was a weird place. For one thing, huge amplifiers were mounted everywhere in all the trees and some were mounted across the road on wires, so to be on the road was to be in this horrible vortex of sound, this pounding, you could barely hear yourself think — rock’n’roll at the highest amps. That day, even before the Angels got there, the cops began arresting anyone who left the compound. I was by the house, Juan was sleeping peacefully in the backseat of the car. It got to be outrageous: the cops were popping people. You could see them about a hundred yards away, but then they would bust somebody very flagrantly, so Allen said, You know, we’ve got to do something about this. I agreed, so with Allen in the passenger’s seat, Juan in the back sleeping, and me driving, we took off after the cops that had just busted another person we knew, who was leaving just to go up to the restaurant on the corner. Then the cops got after us. Allen at the very sight of the cops went into his hum, his om, trying to hum them off. I was talking to them like a journalist would: What’s going on here, Officer? Allen’s humming was supposed to be a Buddhist barrier against the bad vibes the cops were producing and he was doing it very loudly, refusing to speak to them, just “Om! Om! Om!” I had to explain to the cops who he was and why he was doing this. The cops looked into the backseat and said, What is that back there? A child? And I said, Oh, yeah, yeah. That’s my son. With Allen still going, “Om”, we were let go. He was a reasonable cop, I guess — checking out a poet, a journalist and a child. Never did figure Ginsberg out, though. It was like the humming of a bee. It was one of the weirdest scenes I’ve ever been through, but almost every scene with Allen was weird in some way or another.

Interviewer

Did any other Beat Generation authors influence your writing?

Hunter S. Thompson

Jack Kerouac influenced me quite a bit as a writer … in the Arab sense that the enemy of my enemy was my friend. Kerouac taught me that you could get away with writing about drugs and get published. It was possible, and in a symbolic way I expected Kerouac to turn up in Haight — Ashbury for the cause. Ginsberg was there, so it was kind of natural to expect that Kerouac would show up too. But, no. That’s when Kerouac went back to his mother and voted for Barry Goldwater in 1964. That’s when my break with him happened. I wasn’t trying to write like him, but I could see that I could get published like him and make the breakthrough, break through the Eastern establishment ice. That’s the same way I felt about Hemingway when I first learned about him and his writing. I thought, Jesus, some people can do this. Of course Lawrence Ferlinghetti influenced me — both his wonderful poetry and the earnestness of his City Lights bookstore in North Beach.

Interviewer

You left California and the San Francisco scene near its apex. What motivated you to return to Colorado?

Hunter S. Thompson

I still feel needles in my back when I think about all the horrible disasters that would have befallen me if I had permanently moved to San Francisco and rented a big house, joined the company dole, become national — affairs editor for some upstart magazine — that was the plan around 1967. But that would have meant going to work on a regular basis, like nine to five, with an office — I had to pull out.

Interviewer

Warren Hinckle was the first editor who allowed you to write and pursue gonzo journalism — how did you two become acquainted?

Hunter S. Thompson

I met him through his magazine, Ramparts. I met him even before Rolling Stone ever existed. Ramparts was a crossroads of my world in San Francisco, a slicker version of The Nation — with glossy covers and such. Warren had a genius for getting stories that could get placed on the front page of The New York Times. He had a beautiful eye for what story had a high, weird look to it. You know, busting the Defense Department — Ramparts was real left, radical. I paid a lot of attention to them and ended up being a columnist. Ramparts was the scene until some geek withdrew the funding and it collapsed. Jann Wenner, who founded Rolling Stone, actually worked there in the library — he was a copy boy or something.

Interviewer

What’s the appeal of the outlaw writer, such as yourself?

Hunter S. Thompson

I just usually go with my own taste. If I like something, and it happens to be against the law, well, then I might have a problem. But an outlaw can be defined as somebody who lives outside the law, beyond the law, not necessarily against it. And it’s pretty ancient. It goes back to Scandinavian history. People were declared outlaws and they were cast out of the community and sent to foreign lands — exiled. They operated outside the law and were in communities all over Greenland and Iceland, wherever they drifted. Outside the law in the countries they came from — I don’t think they were trying to be outlaws … I was never trying, necessarily, to be an outlaw. It was just the place in which I found myself. By the time I started Hell’s Angels I was riding with them and it was clear that it was no longer possible for me to go back and live within the law. Between Vietnam and weed — a whole generation was criminalized in that time. You realize that you are subject to being busted. A lot of people grew up with that attitude. There were a lot more outlaws than me. I was just a writer. I wasn’t trying to be an outlaw writer. I never heard of that term, somebody else made it up. But we were all outside the law: Kerouac, Miller, Burroughs, Ginsberg, Kesey, I didn’t have a gauge as to who was the worst outlaw. I just recognized allies: my people.

Interviewer

The drug culture. How do you write when you’re under the influence?

Hunter S. Thompson

My theory for years has been to write fast and get through it. I usually write five pages a night and leave them out for my assistant to type in the morning.

Interviewer

This, after a night of drinking and so forth?

Hunter S. Thompson

Oh yes, always, yes. I’ve found that there’s only one thing that I can’t work on and that’s marijuana. Even acid I could work with. The only difference between the sane and the insane is that the sane have the power to lock up the insane. Either you function or you don’t. Functionally insane? If you get paid for being crazy, if you can get paid for running amok and writing about it … I call that sane.

Interviewer

Almost without exception writers we’ve interviewed over the years admit they cannot write under the influence of booze or drugs — or at the least what they’ve done has to be rewritten in the cool of the day. What’s your comment about this?

Hunter S. Thompson

They lie. Or maybe you’ve been interviewing a very narrow spectrum of writers. It’s like saying, Almost without exception women we’ve interviewed over the years swear that they never indulge in sodomy — without saying that you did all your interviews in a nunnery. Did you interview Coleridge? Did you interview Poe? Or Scott Fitzgerald? Or Mark Twain? Or Fred Exley? Did Faulkner tell you that what he was drinking all the time was really iced tea, not whiskey? Please. Who the fuck do you think wrote the Book of Revelation? A bunch of stone — sober clerics?

Interviewer

In 1974 you went to Saigon to cover the war …

Hunter S. Thompson

The war had been part of my life for so long. For more than ten years I’d been beaten and gassed. I wanted to see the end of it. In a way I felt I was paying off a debt.

Interviewer

To whom?

Hunter S. Thompson

I’m not sure. But to be so influenced by the war for so long, to have it so much a part of my life, so many decisions because of it, and then not to be in it, well, that seemed unthinkable.

Interviewer

How long were you there?

Hunter S. Thompson

I was there about a month. It wasn’t really a war. It was over. Nothing like the war David Halberstam and Jonathan Schell and Philip Knightley had been covering. Oh, you could still get killed. A combat photographer, a friend of mine, was killed on the last day of the war. Crazy boys. That’s where I got most of my help. They were the opium smokers.

Interviewer

You hoped to enter Saigon with the Vietcong?

Hunter S. Thompson

I wrote a letter to the Vietcong people, Colonel Giang, hoping they’d let me ride into Saigon on the top of a tank. The VC had their camp by the airport, two hundred people set up for the advancing troops. There was nothing wrong with it. It was good journalism.

Interviewer

Did you ever think of staying in Saigon rather than riding in on a Vietcong tank?

Hunter S. Thompson

Yes, but I had to meet my wife in Bali.

Interviewer

A very good reason. You’re famous for traveling on assignment with an excess of baggage. Did you have books with you?

Hunter S. Thompson

I had some books with me. Graham Greene’s The Quiet American for sure. Phil Knightley’s The First Casualty. Hemingway’s In Our Time. I carried all these seminal documents. Reading The Quiet American gave the Vietnam experience a whole new meaning. I had all sorts of electronic equipment — much too much. Walkie — talkies. I carried a tape recorder. And notebooks. Because of the sweat I couldn’t write with the felt — tip pens I usually use because they would bleed all over the paper. I carried a big notebook — sketchbook size. I’d carry all this stuff in a photographer’s pack over my shoulders. I also carried a .45 automatic. That was for weird drunk soldiers who would wander into our hotel. They were shooting in the streets … someone would fire off a clip right under your window. I think Knightley had one, too. I got mine from someone who was trying to smuggle orphans out of the country. I couldn’t tell if he was on the white slave or the mercy market.

Interviewer

Why only a month in Saigon?

Hunter S. Thompson

The war was over. I’d wanted to go to Saigon in 1971. I’d just started working for Rolling Stone. At a strategy summit meeting that year of all the editors at Big Sur, I was making the argument that Rolling Stone should cover national politics. Cover the campaign. If we were going to cover the culture, to not include politics was stupid. Jann Wenner was the only person who half — agreed with me. The other editors there thought I was insane. I was sort of the wild creature. I would always appear in my robe. For three days I made these passionate pitches to the group. At the end of it I finally had to say, Fuck you, I’ll cover it. I’ll do it. Dramatic moment, looking back on it.

Well, you can’t cover national politics from Saigon. So I moved lock, stock and barrel from here to Washington. Took the dogs. Sandy, my wife, was pregnant. The only guy willing to help me was Timothy Crouse, who at the time was the lowest on the totem pole at Rolling Stone. He had a serious stutter, almost a debilitating stutter, which Jann mocked him for all the time, really cruel to him, which made me stand up for him more and more. He never had written more than a three hundred word piece on some rock’n’roll concert. He was the only one who volunteered to go to Washington. Okay, Timbo. It’s you and me. We’ll kick ass. Life does turn on so many queer things … ball bearings and banana skins … a political reporter instead of a war correspondent.

Interviewer

Crouse eventually wrote a bestseller about the press and the campaign — The Boys on the Bus.

Hunter S. Thompson

He was the Boston stringer for Rolling Stone. He had graduated from Harvard and had an apartment in the middle of Cambridge. Strictly into music at the time. He was the only person who raised his hand in Big Sur. We covered the 1972 campaign. I wrote the main stories and Tim did the sidebars. Then there was that night in Milwaukee when I told him I was sick, too sick to write the main story. I said, Well, Timbo, I hate to tell you this but you’re gonna have to write the main story this week and I’m gonna write the sidebar. He panicked. Very bad stuttering. I felt I had to deal with that. I told him he had to stop stuttering. I told him that it’s not constructive. Goddamn it, spit it out!

Interviewer

Not constructive? Easy for you to say.

Hunter S. Thompson

Well, I saw that he lacked confidence. So I made him write the Wisconsin story, and it was beautiful — suddenly he had confidence.

Interviewer

In your introduction to A Generation of Swine, you state that you spent half your life trying to escape journalism.

Hunter S. Thompson

I always felt that journalism was just a ticket to ride out, that I was basically meant for higher things. Novels. More status in being a novelist. When I went to Puerto Rico in the sixties William Kennedy and I would argue about it. He was the managing editor of the local paper, he was the journalist. I was the writer, the higher calling. I felt so strongly about it that I almost wouldn’t do journalism. I figured in order to be a real writer, I’d have to write novels. That’s why I wrote Rum Diary first. Hell’s Angels started off as just another down — and — out assignment. Then I got over the idea that journalism was a lower calling. Journalism is fun because it offers immediate work. You get hired and at least you can cover the fucking City Hall. It’s exciting. It’s a guaranteed chance to write. It’s a natural place to take refuge in if you’re not selling novels. Writing novels is a lot lonelier work.

My epiphany came in the weeks after the Kentucky Derby fiasco. I’d gone down to Louisville on assignment for Warren Hinkle’s Scanlan’s. A freak from England named Ralph Steadman was there — first time I met him — doing drawings for my story. The lead story. Most depressing days of my life. I’d lie in my tub at the Royalton. I thought I had failed completely as a journalist. I thought it was probably the end of my career. Steadman’s drawings were in place. All I could think of was the white space where my text was supposed to be. Finally, in desperation and embarrassment, I began to rip the pages out of my notebook and give them to a copyboy to take to a fax machine down the street. When I left I was a broken man, failed totally, and convinced I’d be exposed when the stuff came out. It was just a question of when the hammer would fall. I’d had my big chance and I had blown it.

Interviewer

How did Scanlan’s utilize the notebook pages?

Hunter S. Thompson

Well, the article starts out with an organized lead about the arrival at the airport and meeting a guy I told about the Black Panthers coming in, and then it runs amok, disintegrates into flash cuts, a lot of dots.

Interviewer

And the reaction?

Hunter S. Thompson

This wave of praise. This is wonderful … pure gonzo. I heard from friends — Tom Wolfe, Bill Kennedy.

Interviewer

So what, in fact, was learned from that experience?

Hunter S. Thompson

I realized I was on to something: maybe we can have some fun with this journalism … maybe it isn’t this low thing. Of course, I recognized the difference between sending in copy and tearing out the pages of a notebook.

Interviewer

An interesting editorial choice — for Scanlan’s to go ahead with what you sent.

Hunter S. Thompson

They had no choice. There was all that white space.

Interviewer

What is your opinion of editors?

Hunter S. Thompson

There are fewer good editors than good writers. Some of my harshest lessons about writers and editors came from carrying those edited stories around the corridors of Time — Life. I would read the copy on the way up and then I would read it again after the editing. I was curious. I saw some of the most brutal jobs done on the writers. There was a guy there, Roy Alexander, a managing editor … oh God, Alexander would x — out whole leads. And this was after other editors had gone to work on it.

Interviewer

Did anybody do that to your copy?

Hunter S. Thompson

Not for long. Well, I can easily be persuaded that I’m wrong on some point. You don’t sit in the hotel room in Milwaukee and look out the window and see Lake Superior, which I’ve written by mistake. Also, an editor is a person who helps me get what I’ve written to the press. They are necessary evils. If I ever got something in on time, which would mean I’d let it go from this house and liked it … well, that’s never happened in my life … I’ve never sent a piece of anything that’s finished … there’s not even a proper ending to Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. I had several different endings in mind, another chapter or two, one of which involved going to buy a Doberman. But then it went to press — a two — part magazine piece for Rolling Stone.

Interviewer

Could you have added a proper ending when it was published as a book?

Hunter S. Thompson

I could have done that but it would have been wrong. Like rewriting the letters in The Proud Highway.

Interviewer

Would it help if you wrote the ending first?

Hunter S. Thompson

I used to believe that. Most of my stuff is just a series of false leads. I’ll approach a story as a subject and then make a whole bunch of different runs at the lead. They’re all good writing but they don’t connect. So I end up having to string leads together.

Interviewer

By leads, you mean paragraphs.

Hunter S. Thompson

The first paragraph. The last paragraph. That’s where the story is going and how it’s going to end. Or else you’ll go off in a hundred different directions.

Interviewer

And that’s not what happened with Fear and Loathing?

Hunter S. Thompson

No. That was very good journalism.

Interviewer

Your book editor at the time of the earliest stages of what was to become Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was Jim Silberman at Random House — a lot of correspondence between the two of you.

Hunter S. Thompson

The assignment he gave me to do was nearly impossible: to write a book about the Death of the American Dream, which was the working title. I looked first for the answer at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968, but I didn’t find it until 1971 at the Circus — Circus Casino in Las Vegas. Silberman was a good, smart sounding board for me. He believed in me and that meant a lot.

Interviewer

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is one of the great titles. Did that come to you suddenly or did someone suggest it?

Hunter S. Thompson

It’s a good phrase. I noticed it last night in one of my letters from 1969. I’d never seen it before or heard it. People accuse me of stealing it from Kierkegaard or Stendhal. It just seemed like the right phrase. Once you get that kind of title down, once you see it on paper, there’s no way you’re going to change it.

Interviewer

What about Raoul Duke? How did the alter ego come about, and why and when?

Hunter S. Thompson

I started using him originally in what I wrote for Scanlan’s. Raoul comes from Castro’s brother, and Duke, God knows. I probably started using it for some false registration at a hotel. I learned at the Kentucky Derby that it was extremely useful to have a straight man with me, someone to bounce reactions off of. I was fascinated by Ralph Steadman because he was so horrified by most of what he saw in this country. Ugly cops and cowboys and things he’d never seen in England. I used that in the Derby piece and then I began to see it was an extremely valuable device. Sometimes I’d bring Duke in because I wanted to use myself for the other character. I think that started in Hell’s Angels when I knew that I had to have something said exactly right and I couldn’t get any of the fucking Angels to say it right. So I would attribute it to Raoul Duke.

Interviewer

Are the best things written under deadlines?

Hunter S. Thompson

I’m afraid that’s true. I couldn’t imagine, and I don’t say this with any pride, but I really couldn’t imagine writing without a desperate deadline.

Interviewer

Can you give an example?

Hunter S. Thompson

I’d agreed for a long time to write an epitaph for Allen Ginsberg. I was going to go to the memorial in Los Angeles. Then I thought it would be a good idea to have Johnny Depp go and deliver it. And he agreed. A bad deadline situation. What I wrote arrived just before Depp went on stage. He was calling me desperately from a payphone in the halls of the Wadsworth Theater in L.A. So Depp goes out and reads the thing which he just got a half — hour before …

[Thompson asks us if we would like to see the result. He switches on the large screen TV set. Johnny Depp is introduced and speaks from behind a podium.]

This is … from the Good Doctor … it’s hot off the presses: Dr. Thompson sends his regrets. He is suffering from a painful back injury, the result of a fateful meeting with Allen Ginsberg three years ago at a sleazy motel in Boulder, Colorado, when the deceased allegedly flipped Thompson over his back and into an empty swimming pool after a public dispute about drugs. Ginsberg, sixty — nine at the time, accused Thompson, in court papers now permanently sealed because of the poet’s recent death, of ’destroying my health and killing my faith in drugs.’ Ginsberg was hysterically angry, sources said, because Thompson had deliberately and deceitfully lured him into an orgy of substance abuse and random sex that ended after three days and nights when the poet was crushed against the wall by a large woman on roller skates in an all — night Boulder tavern. Then admitted to a local hospital, treated for acute psychosis and massive smoke inhalation, Ginsberg also claimed that Thompson had ’maliciously destroyed my last chance for induction to the poetry hall of fame’ by humiliating him in public, secretly injecting him with drugs and eventually causing him to be jailed for resisting arrest and gross sexual imposition. Dr. Thompson denied the charges, as always, and used the occasion of Ginsberg’s death to denounce him as a dangerous bull — fruit with the brain of an open sore and the conscience of a virus. The famed author said that Ginsberg had come on to him one too many times, and was a hopeless addict. ’He got too strong with all that crank,’ Thompson said. ’When he got that way, being in front of him was like being in front of the Johnstown Flood … Allen had magic,’ he said. ’He could talk with the voice of an angel and dance in your eyes like a fawn. I knew him for thirty years and every time I saw him it was like hearing the music again.’ Thompson added that he was shocked by Ginsberg’s crude charges and violent behavior and would have the alleged court papers buried deeper than Ginsberg’s spleen. ’He was a monster,’ Thompson said. ’He was crazy and queer and small. He was born wrong and he knew it. He was smart but utterly unemployable. The first time I met him in New York he told me that even people who loved him believed he should commit suicide because things would never get better for him. And his poetry professor at Columbia was advising him to get a pre — frontal lobotomy because his brain was getting in his way. Don’t worry, I said, so is mine. I’m getting the same advice. Maybe we should join forces. Hell, if we’re this crazy and dangerous, I think we might have some fun … I spoke to Allen two days before he … died. He was gracious as ever. He said he’d welcome the Grim Reaper … because he knew he could get into his pants.’

[After applause and questions as to how the audience in the theater reacted to the somewhat odd eulogy [They liked it], the interview was continued.]

Interviewer

The lead to Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, We were somewhere near Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold … When did you write that? Did you write that first?

Hunter S. Thompson

No, I have a draft … something else was written first, chronologically, but when I wrote that … well, there are moments … a lot of them happen when nothing else is going right … when you’re being evicted from the hotel a day early in New York or you’ve just lost your girlfriend in Scottsdale. I know when I’m hitting it. I know when I’m on. I can usually tell because the copy’s clean.

Interviewer

Most people … losing a girl in Scottsdale or wherever, would have a drink somewhere and go crazy. It must have something to do with discipline.

Hunter S. Thompson

I never sit down and put on my white shirt and bow — tie and black business coat and think, Well, now’s the time to write. I will simply get into it.

Interviewer

Can you describe a typical writing day?

Hunter S. Thompson

I’d say on a normal day I get up at noon or one. You have to feel sort of overwhelmed, I think, to start. That’s what journalism did teach me … that there is no story unless you’ve written it.

Interviewer

Are there any mnemonic devices that get you going once a deadline is upon you — sharpening pencils, music that you put on, a special place to sit?

Hunter S. Thompson

Bestiality films.

Interviewer

What is your instrument in composing? You are one of the few writers I know who still uses an electric typewriter. What’s wrong with a personal computer?

Hunter S. Thompson

I’ve tried. There is too much temptation to go over the copy and rewrite. I guess I’ve never grown accustomed to the silent, non — clacking of the keys and the temporary words put up on the screen. I like to think that when I type something on this [pointing to the typewriter], when I’m finished with it, it’s good. I haven’t gotten past the second paragraph on a word processor. Never go back and rewrite while you’re working. Keep on it as if it were final.

Interviewer

Do you write for a specific person when you sit down at that machine?

Hunter S. Thompson

No, but I’ve found that the letter form is a good way to get me going. I write letters just to warm up. Some of them are just, Fuck you, I wouldn’t sell that for a thousand dollars, or something, Eat shit and die, and then send it off on the fax. I find the mood or the rhythm through letters, or sometimes either reading something or having something read — it’s just a matter of getting the music.

Interviewer

How long do you continue writing?

Hunter S. Thompson

I’ve been known to go on for five days and five nights.

Interviewer

That’s because of deadlines, or because you’re inspired?

Hunter S. Thompson

Deadlines, usually.

Interviewer

Do you have music on when you write?

Hunter S. Thompson

Through all the Las Vegas stuff I played only one album. I wore out four tapes. The Rolling Stones’ live album, called Get Yer Ya — Ya’s Out with the in — concert version of Sympathy for the Devil.

Interviewer

At one point, Sally Quinn of The Washington Post got after you for writing about specific events, but only 45 percent is actually the truth … how do you reconcile journalism with that?

Hunter S. Thompson

That’s a tough one. I have a hard time with that. I have from the start. I remember an emergency meeting one afternoon at Random House with my editor about Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. What should we tell The New York Times? Should it go on the fiction list or nonfiction? In a lot of cases, and this may be technical exoneration, but I think in almost every case there’s a tip — off that this is a fantasy. I never have quite figured out how the reader is supposed to know the difference. It’s like if you have a sense of humor or not. Now keep in mind I wasn’t trying to write objective journalism, at least not objective according to me. I’d never seen anybody, maybe David Halberstam comes closest, who wrote objective journalism.

Interviewer

You can write anywhere, can’t you? Is there a place you prefer?

Hunter S. Thompson

Well, this is where I prefer now. I’ve created this electronic control center here.

Interviewer

If you could construct a writer, what attributes would you give him?

Hunter S. Thompson

I would say it hurts when you’re right and it hurts when you’re wrong, but it hurts a lot less when you’re right. You have to be right in your judgments. That’s probably the equivalent of what Hemingway said about having a shock — proof shit detector.

Interviewer

In a less abstract sense, would self–discipline be something you would suggest?

Hunter S. Thompson

You’ve got to be able to have pages in the morning. I measure my life in pages. If I have pages at dawn, it’s been a good night. There is no art until it’s on paper, there is no art until it’s sold. If I were a trust — fund baby, if I had any income from anything else … even fucking disability from a war or a pension … I have nothing like that, never did. So, of course, you have to get paid for your work. I envy people who don’t have to …

Interviewer

If you had that fortune sitting in the bank would you still write?

Hunter S. Thompson

Probably not, probably not.

Interviewer

What would you do?

Hunter S. Thompson

Oh … I’d wander around like King Farouk or something. I’d tell editors I was going to write something for them, and probably not do it.