IT’S ABOUT ART, MUSIC & LITERATURE

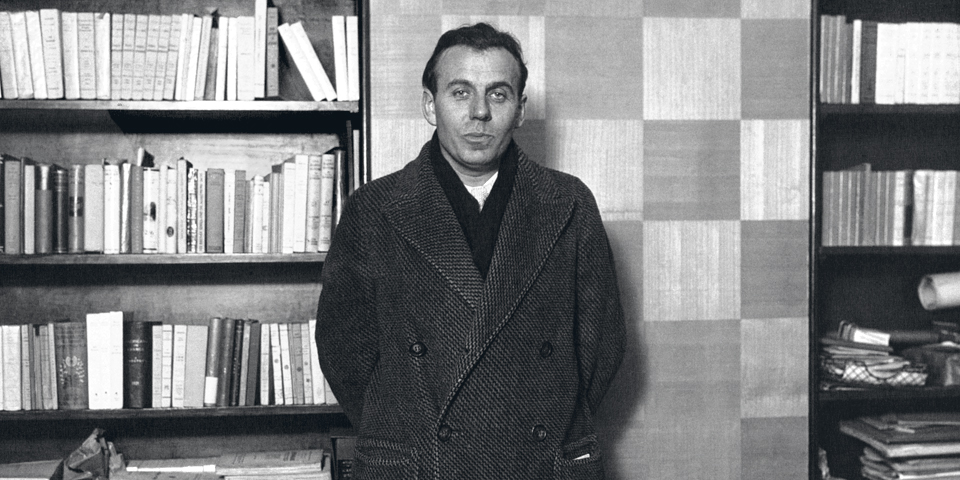

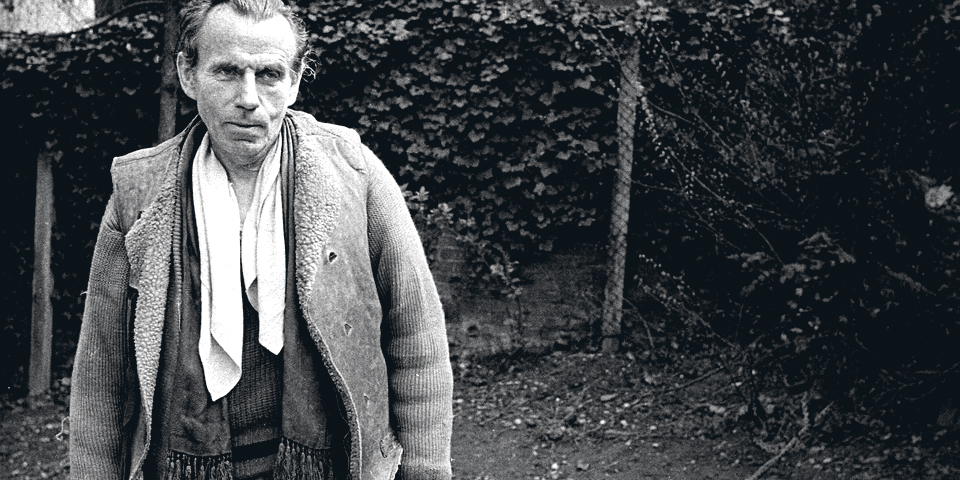

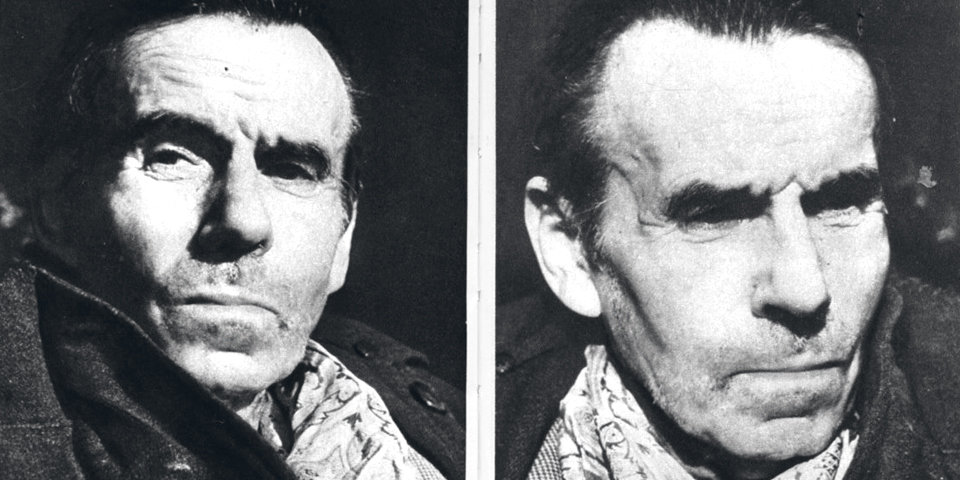

FERDINAND CÉLINE

THE ART OF FICTION

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, pen name of Dr. Louis-Ferdinand Destouches, is best known for his works Voyage au bout de la nuit [Journey to the End of the Night], and Mort à crédit [Death on the Installment Plan]. His highly innovative writing style using Parisian vernacular, vulgarities, and intentionally peppering ellipses throughout the text was used to evoke the cadence of speech.

“I have never voted in my life … I have always known and understood that the idiots are in a majority so it’s certain they will win.”

Interview with Louis Ferdinand Céline [1961]

Louis-Ferdinand Destouches was raised in Paris, in a flat over the shopping arcade where his mother had a lace store. His parents were poor [father a clerk, mother a seamstress]. After an education that included stints in Germany and England, her performed a variety of dead-end jobs before he enlisted in the French cavalry in 1912 two years before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. While serving on the Western Front he was wounded in the head and suffered serious injuries – a crippled arm and headaches that plagued him all his life – but also winning a medal of honour. Released from military service, he studied medicine and emigrated to the USA where he worked as a staff doctor at the newly build Ford plant in Detroit before returning to France and establishing a medical practice among the Parisian poor. Their experiences are featured prominently in his fiction. Although he is often cited as one of the most influential and greatest writers of the twentieth–century, he is certainly a controversial figure. After embracing fascism, he published three antisemitic pamphlets, and vacillated between support and denunciation of Hitler. He fled to Germany and Denmark in 1945 where he was imprisoned for a year and declared a national disgrace. He then received amnesty and returned to Paris in 1951. Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Henry Miller, William Burroughs, and Charles Bukowski have all cited him as an important influence.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

So what can I say to you? I don’t know how to please your readers. Those’re people with whom you’ve got to be gentle … You can’t beat them up. They like us to amuse them without abusing them. Good … Let’s talk. An author doesn’t have so many books in him. Journey to the End of the Night, Death on the Installment Plan — that should’ve been enough … I got into it out of curiosity. Curiosity, that’s expensive. I’ve become a tragical chronicler. Most authors are looking for tragedy without finding it. They remember personal little stories which aren’t tragedy. You’ll say: The Greeks. The tragic Greeks had the impression of speaking with the gods … Well, sure … Christ, it’s not everyday you have a chance to telephone the gods.

Interviewer

And for you the tragic in our times?

Céline

It’s Stalingrad. How’s that for catharsis! The fall of Stalingrad is the finish of Europe. “There” was a cataclysm. The core of it all was Stalingrad. There you can say it was finished and well finished, the white civilization. So all that, it made some noise, some boiling, the guns, the waterfalls. I was in it … I profited off it. I used this stuff. I sell it. Evidently I’ve been mixed up in situations — the Jewish situation — which were none of my business, I had no business being there. Even so I described them … after my fashion.

Interviewer

A fashion that caused a scandal with the appearance of Journey. Your style shook a lot of habits.

Céline

They call that inventing. Take the impressionists. They took their painting one fine day and went to paint outside. They saw how you really lunch on the grass. The musicians worked at it too. From Bach to Debussy there’s a big difference. They’ve caused some revolutions. They’ve stirred the colors, the sounds. For me it’s words, the positions of words. Where French literature’s concerned, there I’m going to be the wise man, make no mistake. We’re pupils of the religions — Catholic, Protestant, Jewish … Well, the Christian religions. Those who directed French education down through the centuries were the Jesuits. They taught us how to make sentences translated from the Latin, well balanced, with a verb, a subject, a complement, a rhythm. In short — here a speech, there a preach, everywhere a sermon! They say of an author, “He knits a nice sentence!”. Me, I say, “It’s unreadable”. They say, “What magnificent theatrical language!” I look, I listen. It’s flat, it’s nothing, it’s nil. Me, I’ve slipped the spoken word into print. In one sole shot.

Interviewer

That’s what you call your “little music”, isn’t it?

Céline

I call it “little music” because I’m modest, but it’s a very hard transformation to achieve. It’s work. It doesn’t seem like anything the way it is, but it’s quality. To do a novel like one of mine you have to write eighty thousand pages in order to get eight hundred. Some people say when talking about me, “There’s natural eloquence … He writes like he talks … Those are everyday words … They’re practically identical … You recognize them”. Well, there, that’s “transformation”. That’s just not the word you’re expecting, not the situation you’re expecting. A word used like that becomes at the same time more intimate and more exact than what you usually find there. You make up your style. It helps to get out what you want to show of yourself.

Interviewer

What are you trying to show?

Céline

Emotion. Savy, the biologist, said something appropriate: In the beginning there was emotion, and the verb wasn’t there at all. When you tickle an amoeba she withdraws, she has emotion, she doesn’t speak but she does have emotion. A baby cries, a horse gallops. Only us, they’ve given us the verb. That gives you the politician, the writer, the prophet. The verb’s horrible. You can’t smell it. But to get to the point where you can translate this emotion, that’s a difficulty no one imagines … It’s ugly … It’s superhuman … It’s a trick that’ll kill a guy.

Interviewer

However, you’ve always approved of the need to write.

Céline

You don’t do anything for free. You’ve got to pay. A story you make up, that isn’t worth anything. The only story that counts is the one you pay for. When it’s paid for, then you’ve got the right to transform it. Otherwise it’s lousy. Me, I work … I have a contract, it’s got to be filled. Only I’m sixty-six years old today, I’m seventy-five percent mutilated. At my age most men have retired. I owe six million to Gallimard … so I’m obliged to keep on going … I already have another novel in the works: always the same stuff … It’s chicken feed. I know a few novels. But novels are a little like lace … an art that disappeared with the convents. Novels can’t fight cars, movies, television, booze. A guy who’s eaten well, who’s escaped the big war, in the evenings gives a peck to the old lady and his day’s finished. Done with.

[Interview, later in 1960]

Interviewer

Do you remember having had a shock, a literary explosion, which marked you?

Céline

Oh, never, no! Me, I started in medicine and I wanted medicine and certainly not literature. Jesus Christ, no! If there are any people who seem to me gifted, I’ve seen it in — always the same — Paul Morand, Ramuz, Barbusse, the guys who were made for it.

Interviewer

In your childhood you didn’t think you’d be a writer?

Céline

Oh, not at all, oh, no, no, no. I had an enormous admiration for doctors. Oh, that seemed extraordinary, that did. Medicine was my passion.

Interviewer

In your childhood, what did a doctor represent?

Céline

Just a fellow who came to the passage Choiseul to see my sick mother, my father. I saw a miraculous guy, I did, who cured, who did surprising things to a body which didn’t feel like working. I found that terrific. He looked very wise. I found it absolutely magical.

Interviewer

And today, what does a doctor represent for you?

Céline

Bah! Now he’s so mistreated by society he has competition from everybody, he has no more prestige, no more prestige. Since he’s dressed up like a gas-station attendant, well, bit by bit, he becomes a gas-station attendant. Eh? He doesn’t have much to say anymore, the housewife has Larousse Médical, and then diseases themselves have lost their prestige, there are fewer of them, so look what’s happened: no syph, no gonorrhea, no typhoid. Antibiotics have taken a lot of the tragedy out of medicine. So there’s no more plague, no more cholera.

Interviewer

And the nervous, mental diseases, are there more of those instead?

Céline

Well, there we can’t do anything at all. Some madnesses kill, but not many. But as for the half-mad, Paris is full of them. There’s a natural need to look for excitement, but obviously all the bottoms you see around town inflame the sex drive to a degree … drive the teen-agers nuts, eh?

Interviewer

When you were working at Ford’s, did you have the impression that the way of life imposed on people who worked there risked aggravating mental disturbances?

Céline

Oh, not at all. No. I had a chief doctor at Ford’s who used to say, “They say chimpanzees pick cotton. I say it’d be better to see some working on the machines”. The sick are preferable, they’re much more attached to the factory than the healthy, the healthy are always quitting, whereas the sick stay at the job very well. But the human problem, now, is not medicine. It’s mainly women who consult doctors. Woman is very troubled, because clearly she has every kind of known weakness. She needs … she wants to stay young. She has her menopause, her periods, the whole genital business, which is very delicate, it makes a martyr out of her, doesn’t it, so this martyr lives anyway, she bleeds, she doesn’t bleed, she goes and gets the doctor, she has operations, she doesn’t have operations, she gets re-operated, then in between she gives birth, she loses her shape, all that’s important. She wants to stay young, keep her figure, well. She doesn’t want to do a thing and she can’t do a thing. She hasn’t any muscle. It’s an immense problem … hardly recognized. It supports the beauty parlors, the quacks, and the druggists. But it doesn’t present an interesting medical situation, woman’s decline. It’s obviously a fading rose, you can’t say it’s a medical problem, or an agricultural problem. In a garden, when you see a rose fade, you accept it. Another one will bloom. Whereas in woman, she doesn’t want to die. That’s the hard part.

Interviewer

Your profession as a doctor brought you a certain number of revelations and experiences you passed on in your books.

Céline

Oh yes, oh yes, I spent thirty-five years doctoring, so it does count a bit. I ran around a lot in my youth. We climbed a lot of stairs, saw a lot of people. It helped me a lot in all ways, I must say. Yes, enormously. But I didn’t write any medical novels, that’s an abominable bore … like Soubiran.

Interviewer

You got your medical calling very early in life, and yet you started out entirely differently.

Céline

Oh, yes. And how! They wanted to make a buyer out of me. A department store salesman! We didn’t have anything, my parents didn’t have the means, don’t you see. I started in poverty, and that’s how I’m finishing.

Interviewer

What was life like for small businesses around 1900?

Céline

Fierce, fierce. In the sense that we hardly had enough to eat, and you had to keep up appearances. For example, we had two shop fronts in the passage Choiseul, but there was always only one lit up because the other was empty. And you had to wash the passage before going to work. My father. That was no joke. Well. My mother had earrings. We always took them to the pawnshop at the end of the month, to pay the gas bill. Oh, no, it was awful.

Interviewer

Did you live a long time in the passage Choiseul?

Céline

Well, eighteen years. Until I joined up. It was extreme poverty. Tougher than poverty, because in poverty you can let yourself go, degenerate, get drunk, but this was poverty which keeps up, dignified poverty. It was terrible. All my life I ate noodles. Because my mother used to repair old lacework. And one thing about old lace is that odors stick to it forever. And you can’t deliver smelly lace! So what didn’t smell? Noodles. I’ve eaten basinfuls of noodles. My mother made noodles by the basinful. Boiled noodles, oh, yes, yes, all my youth, noodles and mush. Stuff that didn’t smell. The kitchen in the passage Choiseul was on the second floor, as big as a cupboard, you got to the second floor by a corkscrew staircase, like this, and you had to go up and down endlessly to see if it was cooking, if it was boiling, if it wasn’t boiling, impossible. My mother was a cripple, one of her legs didn’t work, and she had to climb that staircase. We used to climb it twenty-five times a day. It was some life. An impossible life. And my father was a clerk. He came home at five. He had to do the deliveries for her. Oh, no, that was poverty, dignified poverty.

Interviewer

Did you also feel the harshness of poverty when you went to school?

Céline

We weren’t rich at school. It was a state school, you know, so there weren’t any complexes. Not many inferiority complexes, either. They were all like me, little flea-bitten kids. No, there weren’t any rich people in that place. We knew the rich ones. There were two or three. We worshiped them! My parents used to tell me, those people were rich, the local linen merchant. Mr. Prudhomme. They’d drifted in by mistake, but we recognized them, with awe. In those days we worshiped the rich man! For his wealth! And at the same time we thought he was intelligent.

Interviewer

When and how did you become aware of the injustice it represented?

Céline

Very late, I must confess. After the war. It happened, you see, when I saw people making money while the others were dying in the trenches. You saw it and you couldn’t do anything about it. Then later I was at the League of Nations, and there I saw the light. I really saw the world was ruled by the Golden Calf, by Mammon! Oh, no kidding! Implacably. Social consciousness certainly came to me late. I didn’t have it, I was resigned.

Interviewer

Was your parents’ attitude one of acceptance?

Céline

It was one of frantic acceptance! My mother always used to tell me, “Poor kid, if you didn’t have the rich people [because I already had a few little ideas, as it happened], if there weren’t any rich people we wouldn’t have anything to eat. Rich people have responsibilities”. My mother worshiped rich people, you see. So what do you expect, it colored me too. I wasn’t quite convinced. No. But I didn’t dare have an opinion, no, no. My mother who was in lace up to her neck would never have dreamed of wearing any. That was for the customers. Never. It wasn’t done, you see. Not even the jeweler, he didn’t wear jewels, the jeweler’s wife never wore jewels. I was one of their errand boys. At Robert on the rue Royale, at Lacloche on the rue de la Paix. I was very active in those days. O, la la! I did everything really fast. I’m all gouty now, but in those days I used to beat the Métro. Our feet always hurt. My feet always have hurt. Because we didn’t change our shoes very often, you know. Our shoes were too small and we were getting bigger. I ran all my errands on foot. Yes … Social consciousness … When I was in the cavalry I went to the hunting parties of Prince Orloff and the Duchess of Uzès, and we used to hold the officers’ horses. That was as far as it went. Absolute cattle, we were. It was clearly understood, of course, that was the deal.

Interviewer

Did your mother have much influence on you?

Céline

I have her character. Much more than anything else. She was so hard, she was impossible, that woman. I must say she had some temperament. She didn’t enjoy life, that’s all. Always worried and always in a trance. She worked up to the last minute of her life.

Interviewer

What did she call you? Ferdinand?

Céline

No. Louis. She wanted to see me in a big store, at the Hôtel de Ville, the Louvre. As a buyer. That was the ideal for her. And my father thought so too. Because he’d had so little success with his degree in literature! And my grandfather had a doctorate! They’d had so little success, they used to say, business, he’ll succeed in business.

Interviewer

Couldn’t your father have had a better position teaching?

Céline

Yes, poor man, but here’s what happened: he needed a teaching degree and he only had a general education degree, and he couldn’t go any further because he didn’t have any money. His father had died and left a wife and five children.

Interviewer

And did your father die late in life?

Céline

He died when Journey came out, in 1932.

Interviewer

Before the book came out?

Céline

Yes, just. Oh, he wouldn’t have liked it. What’s more, he was jealous. He didn’t see me as a writer at all. Neither did I, for that matter. We were agreed on at least one point.

Interviewer

And how did your mother react to your books?

Céline

She thought it was dangerous and nasty and it caused trouble. She saw it was going to end very badly. She had a prudent nature.

Interviewer

Did she read your books?

Céline

Oh, she couldn’t, it wasn’t within her reach. She’d have thought it all coarse, and then she didn’t read books, she wasn’t the kind of woman who reads. She didn’t have any vanity at all. She kept on working till her death. I was in prison. I heard she had died. No, I was just arriving in Copenhagen when I heard of her death. A terrible trip, vile, yes — the perfect orchestration. Abominable. But things are only abominable from one side, don’t forget, eh? And, you know … experience is a dim lamp which only lights the one who bears it … and incommunicable … Have to keep that for myself. For me, you only had the right to die when you had a good tale to tell. To enter in, you tell your story and pass on. That’s what Death on the Installment Plan is, symbolically, the reward of life being death. Seeing as … it’s not the good Lord who rules, it’s the devil. Man. Nature’s disgusting, just look at it, bird life, animal life.

Interviewer

When in your life were you happy?

Céline

Bloody well never, I think. Because what you need, getting old … I think if I were given a lot of dough to be free from want — I’d love that — it’d give me the chance to retire and go off somewhere, so I’d not have to work, and be able to watch others. Happiness would be to be alone at the seaside, and then be left in peace. And to eat very little, yes. Almost nothing. A candle. I wouldn’t live with electricity and things. A candle! A candle, and then I’d read the newspaper. Others, I see them agitated, above all excited by ambitions, their life’s a show, the rich swapping invitations to keep up with the performance. I’ve seen it, I lived among society people once — “I say, Gontran, hear what he said to you, oh, Gaston, you really were on form yesterday, eh! Told him what was what, eh! He told me about it again last night! His wife was saying, oh, Gaston surprised us!” It’s a comedy. They spend their time at it. Chasing each other round, meeting at the same golf clubs, the same restaurants.

Interviewer

If you could have it all over again, would you pick your joys outside literature?

Céline

Oh, absolutely! I don’t ask for joy. I don’t feel joy. To enjoy life is a question of temperament, of diet. You have to eat well, drink well, then the days pass quickly, don’t they? Eat and drink well, go for a drive in the car, read a few papers, the day’s soon gone. Your paper, some guests, morning coffee, my God, it’s lunchtime when you’ve had your stroll, eh? See a few friends in the afternoon and the day’s gone. In the evening, bed as usual and shut-eye. And there you are. And the more so with age, things go faster, don’t they? A day’s endless when you’re young, whereas when you grow old it’s very soon over. When you’re retired, a day’s a flash, when you’re a kid it’s very slow.

Interviewer

How would you fill your time if you were retired with income?

Céline

I’d read the paper. I’d take a little walk in a place where no one could see me.

Interviewer

Can you take walks here?

Céline

No, never, no! Better not!

Interviewer

Why not?

Céline

I’d be noticed. I don’t want that. I don’t want to be seen. In a port you disappear. In Le Havre … I shouldn’t think they’d notice a fellow on the docks in Le Havre. You don’t see a thing. An old sailor, an old fool …

Interviewer

And you like boats?

Céline

Oh, yes! Yes! I love watching them. Watching them come and go. That and the jetty, and me, I’m happy. They steam, they go away, they come back, it’s none of your business, eh? No one asks you anything! Yes, and you read the local paper, Le Petit Havrais, and … and that’s it. That’s all. Oh, I’d live my life over differently.

Interviewer

Were there ever any exemplary people, for you? People you’d have liked to imitate?

Céline

No, because that’s all magnificent, all that, I don’t want to be magnificent at all, no desire for all that, I just want to be an ignored old man. Those are the people in the encyclopedias, I don’t want that.

Interviewer

I meant people you might have met in daily life.

Céline

Oh, no, no, no, I always see them conning others. They get on my nerves. No. There I have a kind of modesty from my mother, an absolute insignificance, really absolute! What I’m interested in is being completely ignored. I’ve an appetite, an animal appetite for seclusion. Yes, I’d quite like Boulogne, yes, Boulogne-sur-Mer. I’ve often been to Saint-Malo, but that’s not possible any more. I’m more or less known there. Places people never go …

[Céline’s last interview, June 1, 1961]

Interviewer

In your novels does love hold much importance?

Céline

None. You don’t need any. You’ve got to have modesty when you’re a novelist.

Interviewer

And friendship?

Céline

Don’t mention that either.

Interviewer

Well, do you think you should concentrate on unimportant feelings?

Céline

You’ve got to talk about the job. That’s all that counts. And furthermore, with lots of discretion. It’s talked about with much too much publicity. We’re just publicity objects. It’s repulsive. Time will come for everybody to take a cure of modesty. In literature as well as in everything else. We’re infected by publicity. It’s really ignoble. There’s nothing to do but a “job” and shut up. That’s all. The public looks at it, doesn’t look at it, reads it, or doesn’t read it, and that’s its business. The author only has to disappear.

Interviewer

Do you write for the pleasure of it?

Céline

Not at all, absolutely not. If I had money I’d never write. Article number one.

Interviewer

You don’t write out of love or hate?

Céline

Oh, not at all! That’s my business if I approve of these feelings you’re talking about, love and friendship, but it’s no business of the public’s!

Interviewer

Do your contemporaries interest you?

Céline

Oh, no, not at all. I got interested in them once to try to keep them from running off to war. Anyhow, they didn’t go off to the war, but they came back loaded with glory. Well, me, they shoved me in prison. I messed up in bothering with them. I shouldn’t have bothered. I had only myself to bother with.

Interviewer

In your latest books there’s still a certain number of feelings which reveal you.

Céline

You can reveal yourself no matter what. It’s not difficult.

Interviewer

You mean you want to persuade us there’s nothing of the intimate you in your latest books?

Céline

Oh, no, intimate, no, nothing. There might be one thing, the only one, which is that I don’t know how to play with life. I have a certain superiority over the others who are, after all, rotten, since they’re always in the middle of playing with life. To play with life, that’s to drink, eat, belch, fuck, a whole pile of things that leave a guy nothing, or a broad. Me, I’m not a player, not at all. So, well, that works out fine. I know how to select. I know how to taste, but as the decadent Roman said, It’s not going to the whore house, it’s the not leaving that counts, isn’t it? Me, I’ve been in there — all my life in the whore houses, but I got out quick. I don’t drink. I don’t like eating. All that’s for the shits. I have the right, don’t I? I’ve only got one life: It’s to sleep and to be left alone.

Interviewer

Who are the writers in whom you recognize a real writing talent?

Céline

There are three characters I felt in the big period who were writers. Morand, Ramuz, Barbusse were writers. They had the feel. They were made for it. But the others aren’t made for it. For God’s sake, they’re impostors, they’re bands of impostors, and the impostors are the masters.

Interviewer

Do you think you’re still one of the greatest living writers?

Céline

Oh, not at all. The great writers … I don’t have to screw around with adjectives. First you’ve got to die and when you’re dead, afterwards they classify. First thing you’ve got to be is dead.

Interviewer

Are you convinced posterity will do you justice?

Céline

But, good God, I’m not convinced! Good God, no! And maybe there won’t even be a France then. It’ll be the Chinese or the Berbers doing the inventory and they’ll be plenty bugged by my literature, my style of owl plotting, and my three dots … It’s not hard. I’ve finished, since we’re talking about “literature”. I’ve finished. After Death on the Installment Plan I’ve said everything, and it wasn’t so much.

Interviewer

Do you detest life?

Céline

Well, I can’t say I love it, no. I tolerate it because I’m alive and because I’ve got responsibilities. Without that, I’m pretty much of the pessimist school. I’ve got to hope for something. I don’t hope for nothing. I hope to die as painlessly as possible. Like everyone else. That’s all. That no one suffers for me, because of me. Well, to die peacefully, huh? To die if possible from an infection or, well, I’ll do myself in. That’d still be by far more simple. What’s coming, “that’s” what’s going to be more and more rugged. It’s much more painful to work now than it was just a year ago, and next year it’s going to be tougher than this year. That’s all.

[Interview that same year in which Céline imagines the introduction and end to a film adaptation of Journey to the End of the Night]

Céline

Well, here you are. July 1914. We’re in the avenue du Bois. And here we have three somewhat nervy Parisiennes. Ladies of the time — time of Gyp. So then, for God’s sake, we hear what they’re saying. And along the Avenue du Bois, along the allée cavalière goes a general, his aide-de-camp bringing up the rear, on horseback, of course, on horseback. So the first of the ladies, for God’s sake, “Oh, I say, it’s General de Boisrobert, did you see?” “Yes, I saw”. “He greeted me, didn’t he?” “Yes, yes, he greeted you. I didn’t recognize him. I’m really not interested, you know”. “But the aide de camp, it’s little Boilepère, Oh, he was there yesterday, he’s impossible, don’t show you’ve seen anything, don’t look, don’t look. He was telling us all about the big exercises at Mourmelon, you know! Oh, he said, it means war, I’ll be leaving, I’m going … He’s impossible, isn’t he, with his war … ”

Then you hear music in the distance, ringing, warlike music.

“D’you think so, really?”

“Oh, yes, darling, they’re impossible, with this war of theirs. These military parades in the evenings, what d’you think they look like? It’s ludicrous, it’s comic opera. Last time at Longchamps I saw all those soldiers with stew pots on their heads, sort of helmets, you’d never believe it, it’s so ugly, that’s what they call war, making themselves look ugly. It’s ridiculous, in my opinion, quite ridiculous. Yes, yes, yes, ridiculous. Oh, do look, there’s the attaché, the Spanish Embassy. He’s talking war too, darling, it’s quite appalling, oh, really I’m quite tired of it, we’d do far better to go on a shoot and kill pheasants. Wars nowadays are ridiculous, for heavens’ sake, it’s unthinkable, one just can’t believe in them any more. They sing those stupid songs, no really, like Maurice Chevalier, actually he’s rather funny, he makes everyone laugh”.

So there you are, yes, that’s all.

“Oh, I’d far rather talk about the flower carnival, yes, the flower carnival, it was so pretty, so lovely everywhere. But now they’re going off to war, so stupid, isn’t it, it’s quite impossible, it can’t last”.

Good, okay, we’ve got a curtain-raiser there, we’re in the war. Good. At that point you can move into Paris and show a bus, there are plenty of striking shots, a bus going down toward the Carrefour Drouot, at one point the bus breaks into a gallop, that’s a funny sight to see, the three-horse Madeleine-Bastille bus, yes, get that shot there. Good, right. At that point you go out into the countryside. Take the landscapes in Journey. You’re going to have to read Journey again — what a bore for you. You’ll have to find things in Journey that still exist. The passage Choiseul, you’re sure to be able to take that. And there’ll be Epinay, the climb up to Epinay, that’ll still be there for you. Suresnes, you can take that too, though it’s not the same as it was … And you can take the Tuileries, and the square Louvois, the little street, you ought to get a look at that, see what fits in with your ideas.

Then there’s mobilization. All right. At that point you begin the Journey. This is where the heroes of Journey go off to war — part of the big picture. You’ll need a pile of dough for that …

Then the end.

I’m giving you a dreamy passage here, then maybe you can show a bit of the Meuse countryside, that’s where I began in the war, by the way, a bit of Flanders, good, fine, you just need to look at it, it’s very evocative, and then very softly you begin to let the rumbling of the guns rise up. What you knew the war by, what the people of ’14 knew it by, was the gunfire, from both sides. It was a rolling “blom belolom belom”, it was a mill, grinding our epoch down. That’s to say, you had the line of fire there in front of you, that was where you were going to be written off, it was where they all died. Yes and what you were supposed to do was climb up there with your bayonet. But for the most part it meant shooting and flames. First shooting, then burning. Villages burning, everything burning. First shooting, then butchery.

Show that as best you may, it’s your problem, work it out. I’m relying on little Descaves, there. You need music to go with the sound of the guns. Sinister kind of music, kind of deep Wagnerian music, he can get it out of the music libraries. Music that fits everything. Very few speeches. Very few words. Even for the big scene, even for the three hundred million. Gunfire. “Belombelolom bom”, “tactactac”. Machine guns — they had them already. From the North Sea to Switzerland there was a four-hundred-and-fifty-kilometer strip which never stopped chewing up men from one end to the other. Yes, oh, yes, whenever a guy got there he said, So this is where it happens, this is where the chopper is, eh. That was where we all slaughtered each other. No dreaming there! One million seven hundred thousand died just there. More than a few. With retreats, advances, retreats, louder and louder BOBOOMS, big guns, little guns, not many planes, no, you can show a plane vaguely, but they weren’t much, no, what scared us was the gunfire, pure and simple. The Germans had big guns and they were a big surprise, for the French army, 105’s, we didn’t have any. Okay. And bicycles which you bent in half and folded up.

So to end your story, the Journey, see, it ends, well, it ends as best it can, eh, but still, there is one end, a conclusion, a signature after the Journey, a really lifelike one. The book ends in philosophical language, the book does, but not the film. Here’s how it is for the film. This was one way I saw the end, like this: There’s an old fellow — I think of him as Simon — who looks after the cemetery, the military cemetery. Well, he’s old now, he’s seventy, he’s worn out. And the director of the military cemetery, the curator, he’s a young man and he’s let him know it’s time he retired. Ah, he says, by all means, I’d like nothing better, can’t get about any more. Because you see, they’ve built him a little hut, not far from Verdun, you know, a hut, so this hut, this kind of Nissen hut, he’s turned it into a little café bar at the same time, and he’s got a gramophone, but really, a period gramophone, yes! So in this bar he serves people drinks and he talks, you know, he tells his story, tells it to lots of people, and you see the bar, and people coming in, many people used to come, they don’t come any more, to visit the graves of their dear departed, but after all those tombs of the dear departed he feels pretty old, eh, and it’s a lot of trouble getting there, so much trouble he doesn’t go any more, himself, because he says, I’m too old, I can’t, I can’t move. Walk three kilometers over those furrows, too much bloody trouble, it is, impossible, I’d come back dead, I would, I’m worn out, worn out, I am. And he has an opportunity to say that because the director of the cemetery has found someone to take his place. And who is this someone who’ll take his place? I’ll tell you. It’s … they’re Armenians. A family of Armenians. There’s a father, a mother, and five little children. And what are they doing there? Well, they’d gone to Africa, like all Armenians, and they’d been kicked out of it, and someone told them they could go and hide up north, they’d find a cemetery and a fellow just on the point of quitting and they could take his place. And oh, he says, that’s fine, because the kids are sick, Africa’s too hot for them anyway. So Simon takes them in. The cemetery keeper. He has his peaked cap on and all. Well, he says, you’ll be taking my place. You’ll be none too warm, though. If you want to make a bit of a fire, there’s wood for the fetching, though the wood fire’s just an old stove for his pot, and he says, me, I can’t last any longer, because of all this running around. There used to be the Americans, in the old days. There still are the Americans, too, down under there, you’ll see, you’ll find them … Well, I’ll show you the gate where they come in, it’s not far, hardly a kilometer, but I can’t do it any more — because he limps too, you see, he limps too — I’m wounded, I am, disabled eighty percent after 1914, it makes a difference! I’ll be going to live with my sister. A fine bitch of a woman she was. Lives in Asnières! Dirty slut, she is! She says I’ve got to go, she says I’ve got to but I don’t know that I’ll get on with her, haven’t seen her for thirty years now, I haven’t, dirty slut she was, must be more of a slut than ever by now. She’s married, she says they’ve a room, maybe, I don’t know what I’ll do there, still, can’t stay here, can I, can’t do the job, I can’t do it. There aren’t many doing it nowadays, two or three of them still come, there used to be plenty, they used to come in droves, in the old days, in memory of them all, the French and the English, there are all kinds buried down there, but you’ll see, like they told me, oh, put the crosses right, yes, some have fallen down, of course they have, time does its work, crosses won’t stay up forever, so I put the crosses right as best I could for a long time, but I don’t go any more now, no, no, I can’t, I have to lie down afterwards, you see, I can’t, and lying down here wouldn’t be any pleasure, and I’ve no one with me, so the visitors come and as it happens one good woman, an American, a very old American woman, and she says, “I want to see my old friend John Brown, my dear uncle that died, don’t you have him there?” Oh, he says, it’s all in the registers, wait a moment, I’ll go and have a look, yes, I’ll show you the register, there, and he shows her the register and says, I kept it well, you see, there, can’t say I didn’t do that, eh, now let’s see, Brown, Brown, Brown. Oh, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. Well, you know, it’s down in the Fauvettes cemetery, down there, lady, hard to find, it is. No, no, please, him over there, with his wife and children, very interesting, the grounds are, they’ll put it all in order for you, and I can’t, you see, I can’t, I’ve told you I can’t, it’s no use, madam, and believe me if you try going over there, eh, eh, let me tell you, finding where he is, he’s there all right, in my register, but it’s a long while since I went to look at it, the American one, it’s a long way, two and a half kilometers at least, no, no, let them do it, they’ll do it. I can serve you what there is, though, granadilla juice, lemon. Oh, you’d like a cup of coffee, oh, to be sure, we couldn’t say no to a cup of coffee, I’ll make you a cup of coffee.

And he makes her a cup of coffee, d’you follow, he’s got a nose for a wealthy dame. Well, he says, you see, my sister, over in Asnières, here’s the coffee, a little coffee? Do you know, that reminds me, I’m not so sure she knows how to make it. A trollop, she is, I say it myself. Eh, I don’t know what I’ll do, I don’t, still, have to go, really have to go. So there it is. Yes. I’m going. Yes, I’m really going, I’m going to leave you with them. Don’t be frightened, now [the others are beginning to look scared]. Oh, it’s none too warm here, but just you put some wood on and it warms up, that’s no trouble. Oh, you’ll see, it’s no joke, here. What about a bit of music. Ah, it was a good one, that gramophone there was, a fine one, ah yes, one from the old days, it was, it was a … And he gets out a wind-up thing and they play the old-time records, but really the old-time, eh — Viens poupoule, Ma Tonkinoise — there you are, you see, it’s better with that on, isn’t it, you can play it all summer long, you can, that’ll bring them in again, once they’ve swabbed the place down a bit, just needs doing, eh? Well, madam, going back, are you? Going to Paris, are you? You’ve got a car? Well, now, I must say, that’d be a help, that would, fancy that, eh, going back in a car …