IT’S ABOUT ART, MUSIC & LITERATURE

MAX ERNST

THE SURREALIST REVOLUTION

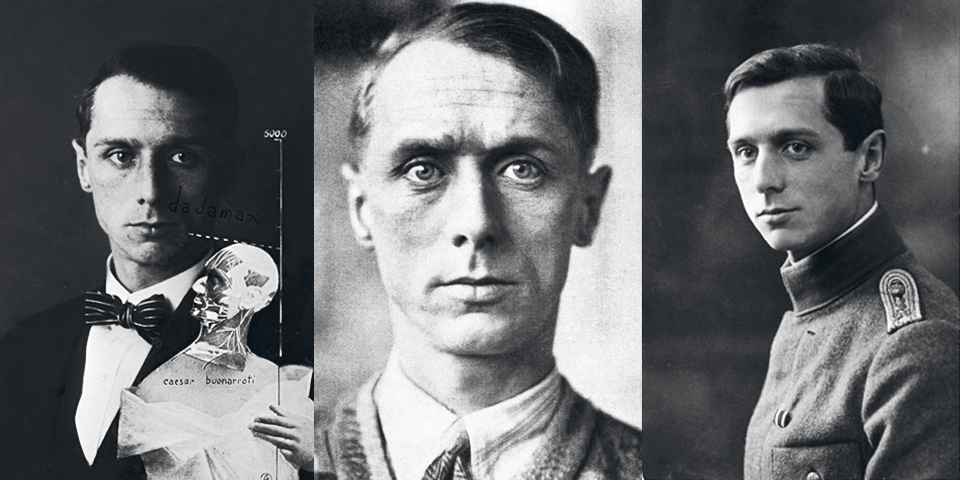

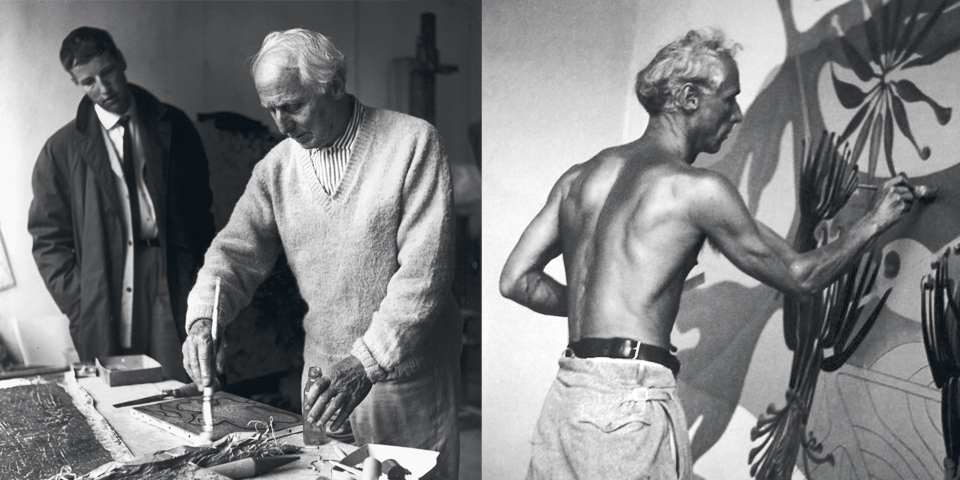

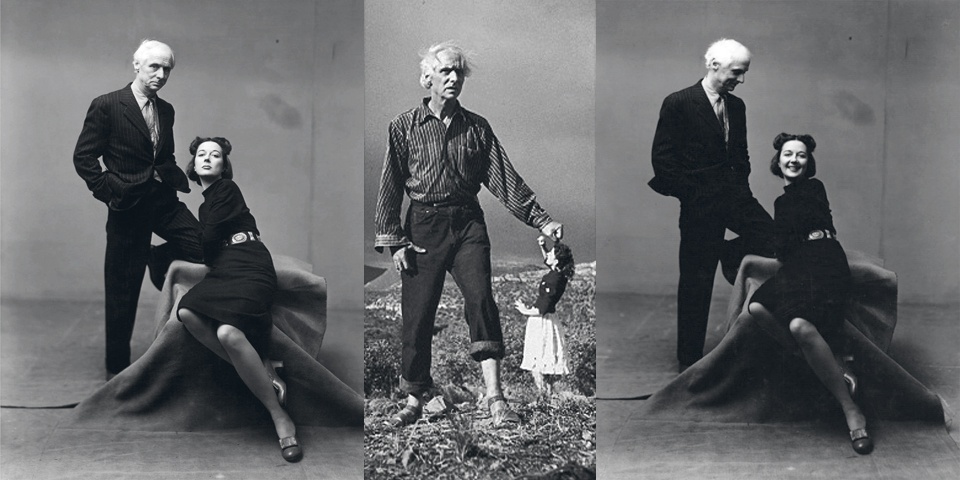

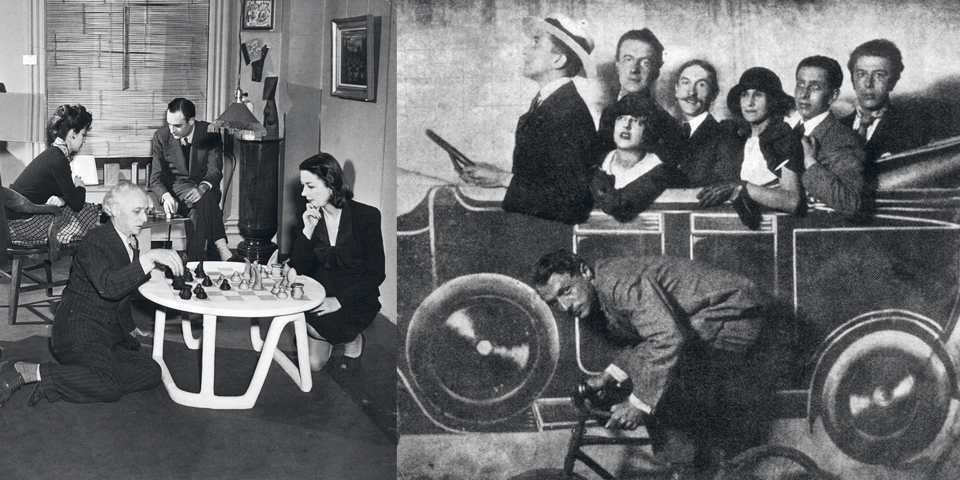

German–born Max Ernst was a provocateur, a shocking and innovative artist who mined his unconscious for dreamlike imagery that mocked social conventions. A soldier in World War I, Ernst emerged deeply traumatized and highly critical of western culture. These charged sentiments directly fed into his vision of the modern world as irrational, an idea that becamethe basis of his artwork. Ernst’s artistic vision, along with his humor and verve come through strongly in his Dada and Surrealists works, Ernst was a pioneer of both movements. Spending the majority of his life in France, during World War II Ernst was categorized as an enemy alien, the United States government affixed the same label when Ernst arrived as a refugee. In later life, in addition to his prolific outpouring of paintings, sculpture, and works–on–paper, Ernst devoted much of his time to playing and studying chess which he revered as an art form. His work with the unconscious, his social commentary, and broad experimentation in both subject and technique remain influential.

Alchemy of The art Image

“Art has nothing to do with taste. Art is not there to be tasted.”

Mein Vagabundieren — Meine Unruhe

Ernst attacked the conventions and traditions of art, all the while possessing a thorough knowledge of European art history. He questioned the sanctity of art by creating non–representational works without clear narratives, by making sport of religious icons, and by formulating new means of creating artworks to express the modern condition. He was profoundly interested in the art of the mentally ill as a means to access primal emotion and unfettered creativity and one of the first artists to apply Sigmund Freud’s dream theories investigate his deep psyche in order to explore the source of his own creativity. While turning inwards unto himself, Ernst was also tapping into the universal unconscious with its common dream imagery. Interested in locating the origin of his own creativity, Ernst attempted to freely paint from his inner psyche and in an attempt to reach a pre–verbal state of being. Doing so unleashed his primal emotions and revealed his personal traumas, which then became the subject of his collages and paintings. This desire to paint from the sub–conscious, also known as automatic painting was central to his Surrealist works and would later influence the Abstract Expressionists.

Max Ernst often responded to the thought of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche in his art in the 1920’s. This study approaches the collage–novel, The Hundred Headless Woman, from the perspective of Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return, suggested by imagery in the novel. The study offers a brief iconographical context for the concept of eternal return, and examines key images in Ernst’s response to this concept. The discordant superimposing of layers of meaning and the refutation of rationality in the novel are considered in terms of the disorientation of time, seriality and the principle of identity implied by the perspectivism of Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return. The study argues that Ernst’s assimilation of Nietzsche’s ideas and concepts is exceptionally sophisticated, and suggests that it significantly anticipates some of the concerns in the reinterpretations of Nietzsche by recent French philosophers.

Max Ernst [1891–1976] created the 147 collages of La femme 100 tetes in 1927, combining images from nineteenth century wood engravings in popular novels, books on natural science and engraved reproductions of art works. The collages were photographically reproduced and printed as ’cliches traites’, and were published as a art novel with short captions under every plate, with an introduction by André Breton [1896–1966] in 1929. The collage–novel was later published in English as The Hundred Headless Woman.

On one level the novel The Hundred Headless Woman is integrally related to the Surrealist interest in Sigmund Freud and the unconscious in the 1920’s. Lucy Lippard, however, stresses the variegated nature of Ernst’s interests: “Yet for his identification with and understanding of the unconscious, the naive, the ’primitive’, Max Ernst remains the product of a highly refined intellectual tradition”. Thematica’y the novel contains a highly cultivated array of references to sources as diverse as Freud’s Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious [1905], Dante’s Divina Commedia [1315], Keats’ La Belle Dame sans Merci [1819], James Joyce’s Ulysses [1922], T.S. Eliot’s Sweeney Among the Nightingales [1920], Le Comte de Lautreamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror [1870], Friedrich Nietzsche’s Die frohliche Wissenschaft [1882], and subjects such as alchemy, mythology, and the natural sciences.

Several authors have examined the meaning and imagery of The Hundred Headless Woman. Major contributions were made b~ Ernst’s friend and biographer Werner Spies , and by Charlotte Stokes in her doctoral dissertation. In various publications Werner Spies approaches the novel from the point of view of the enigmatic identity of Ernst’s hundred headless woman, and Charlotte Stokes has indicated that the novel contains a cohesive story line, based loosely on traditional stories of the life of a hero.

Events in Ernst’s collage–novel are not arranged chronologically. The novel is divided into nine chapters, each comprising a basic thematic unity. As a central theme, the life cycle of the hero begins with birth and youthful experiences, and ends with death and rebirth. The central chapters are based on the journey, or the theme of the wanderer as an essential orientation of the life cycle. The journey proceeds from scenes of physical violence, and continues through scenes of riot, crime, war, destruction and recreation by a mythical race of Titans and the violence of nature. The hero emerges on his life journey in search of the wisdom of the hundred headless woman, the secret that she never yields. Although there are direct, and at times ironic references to Dante’s journey through Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise and his search for Beatrice in the Divina Commedia, the journey in The Hundred Headless Woman does not lead to the divine spheres of Paradise. Instead, this journey leads to a repeated Dionysian process of death and rebirth, a Nietzschean eternal return of the same.

Werner Spies identifies the theme of repetition as a central theme of the collage–novel?, while Charlotte · Stokes considers the theme of repetition to be a device to unify the collages and to control the radically diverse subjects in the novel. Ernst, according to Stokes, verbally establishes the unity of the novel by using the word ’suite’ [continuation] repeatedly throughout the novel, and she considers every instance thereof as “a directional indicator of some sorts”, Werner Spies , furthermore’ also points to an analogy with Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return , suggested by the repetition of print one as the final print with the caption End and continuation , Spies, however, does not explore this association.

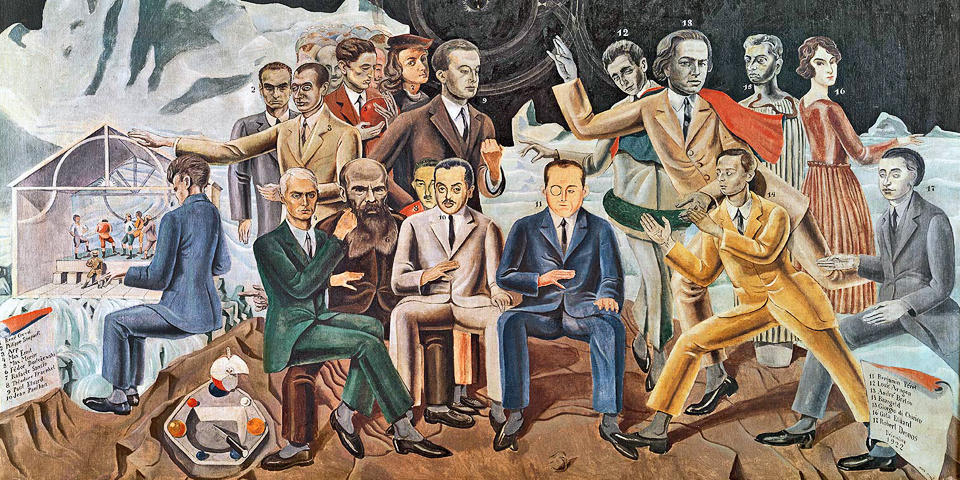

Max Ernst enrolled for a course in philosophy at the University of Bonn in 1909, where he discovered and became enthusiastic about the work of Nietzsche. During the first decade of the century, Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return was fervently discussed in German academic circles, and disagreements about the interpretation of the concept gave rise to a heated debate between Rudolf Steiner, Ernst Horneffer and others in 1900. Ernst participated in the Nietzsche cult in Germany before the First World War, and discussed the philosopher’s ideas in Dada publications in Cologne after the war. In Paris, where Ernst settled in 1922, he had contact with a literary circle that met at the Cafe Savoyard in the Rue Blomet in Montmartre for formal readings from the works of, amongst others, Lautreamont, Sade, Dostojevski and Nietzsche. In the Rue Blomet–group Ernst may have met specialists of Nietzsche’s work, such as Andre Masson [1896–1987], Antonin Artaud [1896–1948], Georges Bataille [1897–1962] and, later, Pierre Klossowski [born 1906], Ernst remained enthusiastic about Nietzsche’s work and he later described his Die frohliche Wissenschaft as essential reading matter: “There, if ever, is a book which speaks to the future. The whole of Surrealism is in it, if you know how to read”. Die frohliche Wissenschaft [translated into English as The Gay Science, or in some editions, The Joyful Wisdom], is also the book in which Nietzsche introduces his concept of the eternal return.

Charlotte Stokes points out iconographical elements in Nietzsche’s works that served as sources for individual collages and images in Ernst’s The Hundred Headless Woman. Her identification of the bird in Ernst’s work, as a derivation from Nietzsche’s Thus spoke Zarathustra is particularly valuable. She observes: “The bird is also a fit alter ego because of the company it keeps. In the form of an eagle it is the companion of the god Zeus and the wanderer Zarathustra. The wanderer , like the wild bird, is free of the regimentation which society imposes on its members and, by his very example, a threat to that regimentation. That the great artist or thinker — like the criminal — is outside and opposed to civilization is an idea which Nietzsche uses to the full in Thus spoke Zarathustra”.

The relevance of this association becomes apparent through an examination of the bird figure in Die frohliche Wissenschaft. Nietzsche dedicates the last section of this work, consisting of a collection of poems, to his metaphorical character ’Prinz Vogelfrei’ [Prince Free as a Bird]. Nietzsche’s Prinz Vogelfrei is a nomadic freethinker and wanderer , and, as an outlaw, is also a criminal figure, These are essential characteristics of Ernst’s heroic figure in The Hundred Headless Woman. Nietzsche describes Prinz Vogelfrei as: “ … that unity of singer, knight and free spirit … an exuberant dancing song in which, if I may say so, one dances right over morality.”

The image of the bird appears in The Hundred Headless Woman for the first time in Ernst’s work, as Loplop. The name of Ernst’s persona, Loplop Bird–Superior, CDer Ubervogel’ or ’Vogeloberse’] is ppossibly derived from Nietzsche’s übermensch. Loplop Bird Superior, the nomadic Prinz Vogelfrei and the wanderer through the journey of the novel are equivalent images for the hero in Ernst’s novel.

Charlotte Stokes argues that Ernst associates Nietzsche’s image of ’Der Wanderer’ with his own participation in the German association ’Der Wandersvogel’. Ernst followed this youth movement in a wanderer’s journey from the Rhineland to Holland in 1906. Stokes shows that the concept of the wanderer has a psxchological significance to Ernst himself. This was already claimed by André Breton in 1942, when he ascribed the following principle to Ernst: Second Commandment — “Wander, the wings of augury wi’ attach themselves to your heels”.

Charlotte Stokes identification of sources from Nietzsche’s works helps clarify the meaning of central images in Max Ernst’s The Hundred Headless Woman. Yet more specific iconographical concurrences between Ernst’s collage–novel and Nietzsche’s Die frohliche Wissenschaft should be noted. These iconographical analogies serve to reinforce the more essential analogy with Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return.

Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return of the same, or of the eternal recurrence, is a concept of the unconditional and infinitely repeated circular course of a things. The concept refers back to a tradition of metaphorical images of wisdom, often symbolised by the circle or the double circle. Nietzsche’s own sources for his treatment of the eternal return extend back to notions of unity and harmony with nature in Eastern mysticism, to pre–Socratic philosophy , to Plato’s view of the double circle of the soul and the cosmic sphere adopted in the Timaeus, and to aspects of Christian thought and the Renaissance tradition.

Nietzsche was markedly influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer’s Parerga und Paralipomena and also by passages in the Letzte Gedichte und Gedanken von Heinrich Heine, published in 1869. The imagery of the eternal return can be associated with the Romantic quest for unity and oneness with the universe. In Thus spoke Zarathustra, the eternal return is announced as the ring of existence by Zarathustra who is the advocate of the circle and the teacher of the eternal recurrence. The eternal return is also repeatedly called the wedding ring of rings — the ring of Recurrence.

Although strikingly similar to many aspects of mystic thought and metaphysical philosophy, Nietzsche’s treatment of the concept is differentiated by, for instance, his refusal to embrace conventional ethical dimensions of the eternal return. As a supra–historical view — according to Walter Kaufmann — Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return also opposes Immanuel Kant’s transcendental view of endless improvement and immortality set forth in his Critique of Practical Reason, as well as G.W.F. Hegel’s conception of infinite progress or the ’ Bad Infinite’ in his Encyklopadie der philosophischern Wisssenschaften und Grundrisse.

More than merely a concept of harmony, Nietzsche’s eternal return is also an extreme repudiation of any depreciation of the moment or of direct experience. Consequently, as Bernd Magnus points out the eternal return is an attitude towards life , rather than a literal concept of the recurrence of time.

Nietzsche describes the eternal return a’s both the m·Jst cultivating, but also the most nihilistic idea: “To endure the idea of the recurrence one needs: freedom from morality new means against the fact of pain, … the enjoyment of all kinds of uncertainty, the experimentalism as a counterweight to this extreme fatalism, abolition of the concept of necessity, abolition of the “will”, abolition of “knowledge” in itself, greatest elevation of the consciousness of strength in man, as he creates the overman [übermensch].”

The eternal return is a central concept in Nietzsche’s thought. It is essentially related to other concepts, for instance heroism, the übermensch, nomadic wandering, transgressive criminality, self–sacrifice, Dionysian destruction and recreation, tragedy, silence, perspectivism and the discontinuity df consciousness. Max Ernst refers to a variety of these related concepts and constantly adopts metaphors and images that are derived from Nietzsche’s works.

Aspects of the heroic endurance of tragedy are essential to Max Ernst’s approach to the eternal return. When Nietzsche introduces the eternal return for the first time in Die frohliche Wissenschaft, the concept is announced as the moment of the birth of tragedy, and “the heaviest burden”. Furthermore, the eternal return is also a tremendous moment, and in Thus spoke Zarathustra it is also a flash of lightning: “My wisdom has long collected itself like a cloud, it is growing stiller and darker. Thus does every wisdom that shall one day give birth to lightnings. I do not want to be light for these men of the present, or be called light by them. These men — I want to blind: lightning of my wisdom! Put out their eyes!”

In a discussion with Life — metaphorically as the figure of a woman — Nietzsche’s Zarathustra exclaims: “If I be a prophet and full of that prophetic spirit that wanders on high ranges between two seas, wanders between past and future like a heavy cloud, … ready for lightning in its dark bosom, … pregnant with lightnings which affirm … In truth, he who wants to kindle the light of the future must hang long over the mountains like a heavy storm! Oh how should I not lust for eternity and for the wedding ring of rings — the Ring of Recurrence!”.

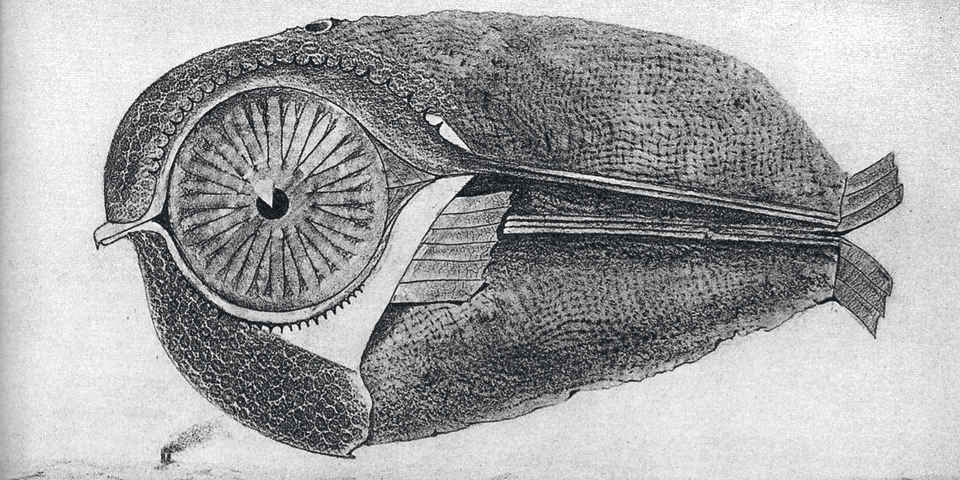

In The Hundred Headless Woman Ernst repeatedly uses the eternal return [translated into French as Le cercle vicieux the vicious circle] — as the wheel of poison. It also functions as a ring or double rings, as a sphere, as wheels, egg–shaped spheres, a phantom globe, or a huge eye. In addition Ernst uses the double ring of eternal return that emerges in a flash of lightning from heavy clouds hanging over the sea and over the mountains like a heavy storm. The quoted description of the eternal return in Thus spoke Zarathustra is closely echoed in a plate captioned: “Truth will remain simple, and gigantic wheels will ride the bitter waves.”

In Ernst’s novel there is a distinct association between the ring of rings of eternal return and the figure of the hundred headless woman, “ … living alone on her phantom globe, beautiful and dressed in her dreams”.

Georges Bataille, whom Ernst might have met at the Rue Blomet–group after 1925, became a major commentator on Nietzsche’s work in France in the 1930’s. In the 1920’s and 1930’s he was the leading figure in a group that included Nietzsche specialists such as Andre Masson and Pierre Klossowski. Bataille wrote a novel W.C. as a dedication to Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return in 1926. Bataille repeatedly uses images for Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return, that are closely akin to those found In Ernst’s The Hundred Headless Woman. W.C. was destroyed before it could be published, but is partly retained in Bataille ’ s short story L’Anus Solair [fhe Solar Anus] of 1927, and is echoed again in the novel L’Histoire de L’œil [Story of the Eye], privately published in 1928. In L’Anus Solair Bataille uses the double ring as an image of the eternal return: “The planetary system that turns in space like a rigid disk, and whose centers also move, describing an infinitely larger circle, only move away continuously from their own position in order to return to it, completing their rotation”.

Although Ernst often followed Bataille’s imagery, it is not known whether he was familiar with the story L’Anus Solair or the unpublished novel W.C. in 1927. However, Ernst’s and Bataille’s images for Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return are strikingly similar at that stage. In 1943 Bataille describes a drawing that was used for W. C. in 1926. According to the description, the drawing, probably by Andre Masson, anticipates key aspects of a particular plate in The Hundred Headless Woman: “A drawing for W.C showed an eye [the scaffold’s eye]. Solitary, solar, bristling with lashes, it gazed from the lunette of a guillotine. The drawing was named Eternal Recurrence, and its horrible machine was the cross–beam, gymnastic gallows, portico, coming from the horizon, the road to eternity passed through it.”

Nietzsche’s image of the putting out of eyes or blinding through the lighting of the wisdom of the eternal return A is repeatedly used by Max Ernst, the refrain “The eye without eyes, the hundred headless woman keeps her secret”, captions most of these plates. Finally the torso of the hundred headless woman becomes a huge eye, while the hero stares eyeless into the double ring of the all–seeing eye. A dancing acrobatic figure in the background , recamng Bataille’s description of the drawing for W.C., also suggests a discussion of the eternal return in Thus spoke Zarathustra: “Lately I gazed into your eyes, o Life: I saw gold glittering in your eyes of night … at my feet, my dancing–mad feet, you threw a glance, a lau.ghing, questioning, melting tossing glance.”

The concept of eternal return serves to explain many scenes of violence and tragedy in The Hundred Headless Woman, as well as the heroic wisdom of Ernst’s wanderer on his quest for the secret of the hundred headless woman. Martin Heidegger points out that tragedy and silence are distinctive qualities of Nietzsche’s eternal return, and that these qualities are already associated with each other when the concept is introduced in Die frohliche Wissenschaft: “Tragedy prevails where the frightful is affirmed as the opposite that is intrinsically proper to the beautiful. He [the übermensch] is silent inasmuch as he is communing with his own soul alone, because he has found what defines him, has become who he is.”

In The Hundred Headless Woman, too, tragedy and silence are repeatedly at variance in the scenes of individual prints. For instance in plate 79, “Truth will remain simple and gigantic wheels will ride the bitter waves”, the thunderbolt of the wheel of eternal return is contrasted with the serenity ofthe hundred headless woman. Contrasts of serenity and tragic destruction appear throughout the series in various scenes. The variance is also part of the total composition of the series. Contrasts of violence and silence are characteristic of the life — journey of the hero. These contrasts echo the relation between the frightful Dionysus and the serene Apollo in Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. Nietzsche’s notion of a Dionysian destructive and recreative cycle is essentially related to his concept of the eternal return. Bataille’s friend Pierre Klossowski pointed out: “The divine vicious circle is only a name for the sign that here takes on a divine countenance, under the aspect of Dionysus: Nietzschean thought breathes. freely in relation to a divine and fabulous countenance.”

Dionysian heroism in Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return, is implied by the image of the overman, the übermensch, which is necessarily part of the experience of the eternal return. Nietzsche’s übermensch has often been interpreted as an ideal–type superman, and this was especially the case in the German Nietzsche cult in which Ernst participated before the First World War.

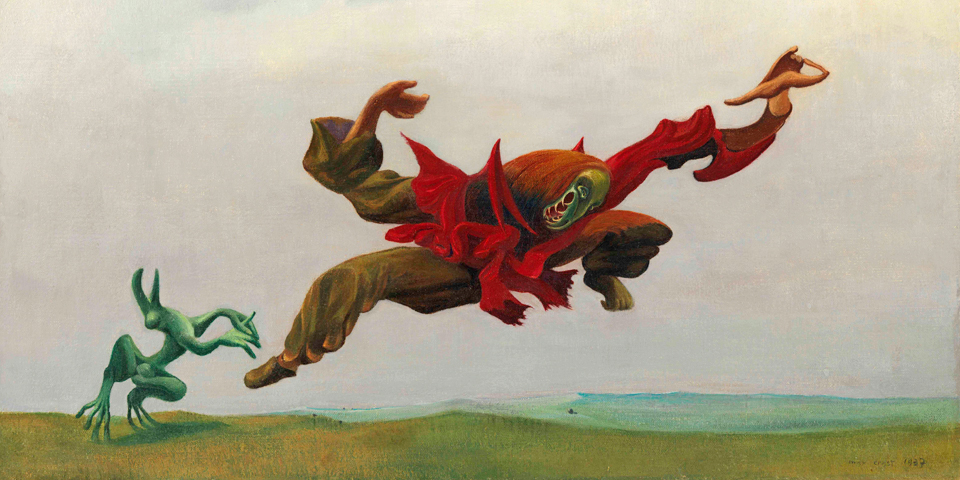

The übermensch may be construed instead as an attitude towards life in which all aspects of life are unconditionally affirmed, an attitude that wills the eternalisation of every moment of life. Ernst, accordingly, stresses the heroic qualities of the protagonist in his novel rather than an idealistic superiority. Ernst’s heroic figure in the novel often appears as Loplop, the Bird Superior. As a person a, Loplop corresponds to aspects of the übermensch. In a discussion of Loplop in 1937, Ernst suggests both the qualities of tragedy and serenity in this persona: “After having composed my novel La femme 100 tetes with systematic violence, I was visited nearly every day by the Bird Superior, named Loplop, an extraordinary phantom of model fidelity who attached himself to my person.”

Like Nietzsche’s übermensch, he is constantly susceptible to shifts of identity. As such he appears as a flying figure, as a bird, as a Titan, as a blind person, as an old man and later again as a baby. In these roles he is identified with both serenity and the tragedy of destruction, echoing Nietzsche’s Dionysus figure and the aesthetics of Dionysian destruction and recreation. Through the continual emphasis on the enigmatic nature of the hero, his identity, like that of Nietzsche’s übermensch and Dionysus, is never precisely determined. In this sense the principle of identity of the hero becomes decentralised, a further aspect of his nomadic nature.

In the same sense that the hero is associated with both tragedy and serenity, criminality and self–sacrifice too, are also constantly present as aspects of his enigmatic identity. In the caption of the first plate of the novel, Ernst announces the theme: Crime or miracle: “A complete man”. Here the flying figure, born from the sphere of the eternal return, descends to the earth like Nietzsche’s heroic figure in Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, who addresses the sun at the moment of the birth of tragedy and the eternal return: “I am weary of my wisdom, like the bee that hath gathered too much honey, I need hands outstretched to take it. Therefore must I descend into the deep, as thou doest in the evening, when thou goest behind the sea and givest light also to the netherworld, thou most rich star! Like thee must I go down, as men say, to whom I shall descend. Bless me then, thou tranquil eye.”

In associating the eternal return with a descent, Nietzsche links the concept with the theme of self–sacrifice. The criminality of Ernst’s hero is likewise linked with the theme of self–sacrifice, anticipating Georges Bataille’s and Andre Masson’s interpretation of Nietzsche in the 1930’S. The descent into the nether world in Ernst’s novel is associated with the descent into the unconscious. The journey of the novel is also a journey through a Freudian unconscious, relinquishing the reason and order of consciousness. Like Prinz Vogelfrei the criminal hero sacrifices himself to a nomadic journey outside the delineated order of conscious existence. In a plate with the caption Fantomas, Dante and Jules Verne, three figures are portrayed in a journey in an air–balloon, suggesting the sphere of the eternal return. The balloon repeats the image of the sphere of the eternal return from which the hero descends in the beginning and at the end of the novel. In the plate Fantomas, Dante and Jules Verne a journey through the metaphorical sphere of the eternal return is suggested as one possible layer of meaning. Dante’s Divina Commedia and Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth are both, in Freudian terms, metaphors for the journey through the psyche, the journey to self–integration and completeness. It is significant to notice that Freud and Nietzsche were associated with each other as regards the unconscious and the supra–individual in the Surrealist journal Minotaure in 1933.

In his essay Beyond Painting of 1937, Ernst associates his novel The Hundred Headless Woman with the Comte de Lautreamont’s character Maldoror from his prose–poem Les Chants de Maldoror [1870]. The Surrealists associated Maldoror with the character F antomas from the popular series of short stories publistled by Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain in Paris between 1912 and 1914. Pierre Souvestre’s film, Fantomas appeared in 1918, and in the late 1920’s the character was still very popular with the Surrealists. As an anarchist outside the norms of society, Fantomas represents the heroic criminal who revaluates the concept of crime. Furthermore, the early French psychoanalytic movement, founded in 1926, was at the time particularly concerned with the theme of criminality. Debates and discourses in legislative and psychoanalytic circles about criteria for determining a criminal’s responsibility for his crime, became a forum for a more general philosophical questioning of the Cartesian notion of rationality and subjectivity. Ernst, who had a specialised knowledge of the psychoanalytic methods of Freud, echoes an early awareness of the questions pursued in this movement, and in 1937 he was to identify the very techni~ue of his collages as a critique of the subject.

Through the association with Jules Verne and Dante in The Hundred Headless Woman, Fantomas’ journey to the interior is a journey outside the rules and norms of civilisation and society. This clearly suggests Nietzsche’s übermensch and the nomadic wanderer and Prinz Vogelfrei which are precedents for Ernst’s Loplop. When Ernst, therefore, announces the theme of Crime or miracle, a complete man, self–integration also implies the transgressive and anarchistic aspects of the journey to the interior. It implies a nomadic journey through the labyrinthean consequences of the unconscious and the eternal return. The exclusion of the nomadic hero from the rules and norms of society, and of its protection, is part of the self–sacrifice of Ernst’s hero, often expressed in the novel as the mutilation of sight.

It is also part of the hero’s criminality, his serenity in scenes of anarchy and violence. In this sense Ernst’s novel significantly anticipates the Dionysian theme in the image of the Minotaur in Surrealist art of the 1930’s.

André Breton, who never liked Nietzsche’s work, and once called Nietzsche, “what I detest the most”, hardly ever acknowledged this philosopher. On the one occasion that Breton took cognisance of Nietzsche’s importance to Surrealism, this was in an examination of the works of Max Ernst. Breton, discussing the need for a Surrealist myth, ascribes to Nietzsche a position equal to that of Rimbaud, Sade and Lautreamont — all figures somehow associated with criminality. In 1930, however, shortly after Ernst published The Hundred Headless Woman with an introduction by Breton, Breton accepted a translation of one of Nietzsche’s letters for publication in the magazine Le Surrealism au service de la revolution. The same letter was to appear again in Breton’s anthology of black humour, Anthologie de I’humour noir in 1937. The references in the letter have a bearing on the content of Ernst’s The Hundred Headless Woman.

In the letter that Nietzsche addressed to Jacob Burckhardt, his colleague in Basel in the 1870’s, Nietzsche uses various images of creativity, and writes: ‘Dear Professor: “At long last I would much rather be a Professor in Basel than God. But I did not dare to carry my private egotism so far as to give up the creation of the world on its account. You see, one has to bring sacrifices, where–ever and however one lives”’. The letter, one of Nietzsche’s last, was written after his mental collapse had probably already occurred. If Ernst shared Breton’s interest in the letter as an instance of black humour, it would merely serve to reinforce his interest in Freud’s Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious at the time. The blasphemous joke, in Freudian terms, is an important device in the mechanism of displacement.

In addition to his association between creativity and self–sacrifice, Nietzsche also links creativity with criminality in the letter to Burckhardt: “Since I am condemned to entertain the next eternity with cracking bad jokes, I am occupied here with writing which leaves really nothing to be desired … and to give you an idea of how harmless I can be, listen to the first of my two bad jokes … I want to give my Parisians whom I love a new concept, that of the decent criminal … a gentleman criminal too.”

A reversal of values is central to Nietzsche’s thought, and the idea of the criminal nature of creativity already finds expression in his earliest work, The Birth of Tragedy. Significantly, the Dionysian criminals in this work are represented by the race of Titans and by Oedipus. The Titans appear in The Hundred Headless Woman, disrupting laundries and restaurants. Finally Ernst associates the Titans with blindness and the precious vision of the ’eternal return,. Of Oedipus, Nietzsche writes in The Birth of Tragedy: “Because of his excessive wisdom, which could solve the riddle of the Sphinx, Oedipus must be tPelunged into a bewildering vortex of crime.”

Oedipus is a central theme in Ernst’s art, dating from his Oedipus Rex of 1922. As the blinded tragic hero, he is constantly associated with Ernst’s symbolism of the eye. In The Hundred Headless Woman the putting out of eyes is an image that is repeatedly used. In Une Semaine de bonte of 1933, Oedipus also appears as the bird Loplop, and as a jail breaker.

Nietzsche, furthermore, associates the criminal figure with his concept of the übermensch. In his last work, Ecce Homo, he writes: “Zarathustra, the first psychologist of the good, is — consequently — a friend of the evil. He does not conceal the fact that his type of man … is übermensch precisely in its relation to the good — that the good and the just would call his übermensch devil.”

The criminal aspects of übermenschlichkeit are exemplified by Ernst in various scenes of tragedy, self–sacrifice, Satanism, and sacrilege in the novel The Hundred Headless Woman. In 1937, discussing the novel, Ernst writes: “I had already said hello to Satan.”

Crime and wisdom, however closely related by Ernst, are never instrumental in revealing the secret of the hundred headless woman in the novel. Associated with the’ eterna return’, tragedy and serenity, she is at the same time all–seeing eye, and the wheel of poison. In the sense that the principle of identity of the hero in the novel is decentralised, the identity of the figure of the hundred headless woman, living on her phantom globe, is even more enigmatic, evasive and illusory. This is already suggested by the incongruous contradiction of singular and plural in the title The Hundred Headless Woman. In one image Ernst makes her appear literally headless, her face a black void in the robes of her headdress. In the imagery of the headless woman Ernst anticipates BataiIle and Masson’s Nietzschean imagery of the headless Dionysian figure in the journal Acephale. Between 1938 and 1939 the journal was dedicated to Nietzsche’s philosophy.

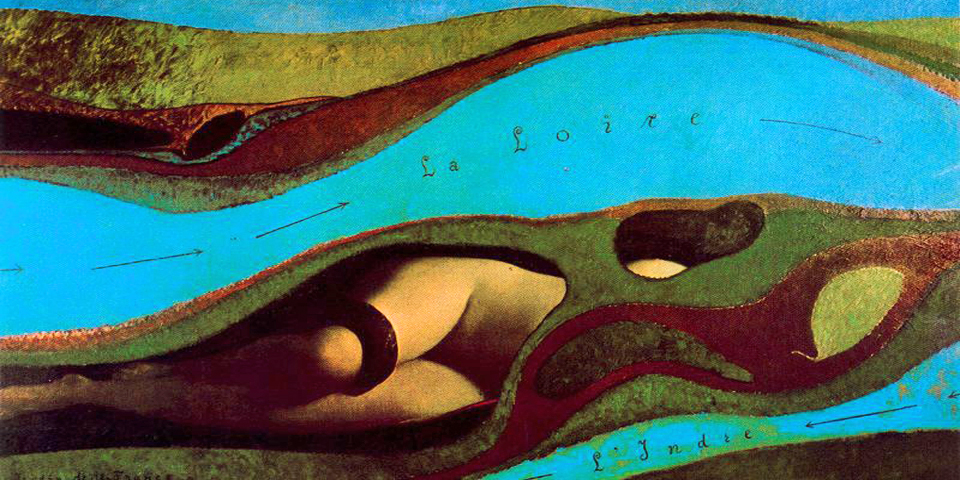

In a scene with the caption, “ … at every stop” , Ernst uses a nineteenth century romantic image adopted before by both Arthur Schopenhauer and Nietzsche as an image of the illusory nature of reality. Quoting Schopenhauer, Nietzsche writes in The Birth of Tragedy: “Even as an immense, raging sea, assailed by huge wave crests, a man sits in a little rowboat trusting his frail craft, so, amidst the furious torments of this world, the individual sits tranquilly, supported by the principium individuationis and relying on it”. The erroneous truth of the Apollonian principle of individuation in this passage, is shown in its relation to the sea as the multiplicity of the Dionysian substratum.

Drifting on the deceptive calm of the boundless sea in the seascape, “at every stop”, the frail craft is guarded over by the circle of the eternal return, the ’phantom globe’ of the hundred headless woman in the novel. In various other seascapes in the novel, however, the sea itself bursts forth into a raging activity of chaos, often washing everything out of its way except the incongruous serenity of the figure of the hundred headless woman. Significantly, the raging sea is twice called jubilant, echoing Nietzsche’s Dionysian sphere of excess and ecstasy [Rausch]. Ernst’s contrasted raging sea and the serenity of the figure of the hundred headless woman, is closely analogous to the terror and jubilation of Dionysus and the calm repose of Apollo in The Birth of Tragedy.

In a passage from Die frohliche Wissenschaft, Nietzsche returns to the image of the boat on the sea, and then associates the secret of womanhood with the white sail of the boat. This passage is significant in terms of the question of the identity of the figure of the hundred headless woman and her secret throughout the novel. Ernst, who regarded Die frohliche Wissenschaft as very important reading matter, quoted from a paragraph preceding this passage in Der Ventilator in 1919. He could, therefore, hardly have missed the text that is a key passage in Die fröhliche Wissenschaft. In the passage, Nietzsche writes: “Here I sit in the midst of the surging of the breakers, whose white flames fork up to my feet, — from all sides there is howling, threatening, crying and screaming at me … Then, suddenly, as if born out of nothingness, there appears before the portal of this hellish labyrinth, … a great sailing–ship gliding silently along like a ghost … has aIl the repose and silence in the world embarked here? Does my happiness itself sit in this quiet place, my happier ego, my second immorta ised self? … Similar to the ship, which, with its white sails, like an immense butterfly, passes over the dark sea! Yes! Passing over existence! … When a man is in the midst of his hubbub, … he there sees perhaps calm, enchanting beings glide past him, … they are women. He almost thinks that there with the women dwells his better self, … and life itself a dream of life. But still … there is also in the most beautiful sailing–ship so much noise and bustling … The enchantment and the most powerful effect of woman is, to use the language of philosophers, and effect at a distance … primarily and above all–distance!”

The woman, as distance, is echoed in Ernst’s repeated association between her and perturbation, phantom, or secret. The white sails of the ship again suggest the analogy between the figure of the hundred headless woman, and Nietzsche’s image of Apollonian illusion.

In an important commentary on the particularpassagefrom Nietzsche, Jacques Derrida emphasises the enigmatic nature of Nietzsche’s image of hypothetical womanhood: “Perhaps woman — a non–identity, a non–figure, a simulacrum — is distance’s very chasm, the out–distancing of distance, the interval’s cadence … There is no such thing as the essence of woman because woman averts, she is averted of herself.” Derrida accentuates Nietzsche’s image of woman as an image of truth, truth as distance without essence or any determined identity. The decentralisation of truth is essential to Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return and his analoguous concept of perspectivism. For Ernst, too, the figure of the hundred headless woman who never yields her secret, merely leads, continuously, to rebirth through the eternal return.

The text from Die frohliche Wissenschaft quoted by Ernst in Der Ventilator in 1919, supports Ernst’s interest in the perspectival approach to the eternal return, and is worth repeating: “The name and appearance, the importance, the usual measure and weight of things — each being in origin most frequently an error and arbitrariness thrown over the things like a garment, and quite alien to their essence and even their exterior — have gradually … grown as it were on and into things and become their very body, the appearance at the very beginning becomes almost always the essence in the end, and operates as the essence! What a fool he would be who would think it enough to refer here to this origin and this nebulous veil of illusion … let us not forget this: it suffices to create new names and valuations and probabilities in order in the long run to create new things.”

The passage corresponds to the interest in Nietzsche’s work in the Dada circles, but already reflects Ernst’s interest in the arbitrary and incongruous nature of the illusory substrate of reality, as set forth in Nietzsche’s work.

M.E. Warlick has observed the difficulties that commentators experience when endeavouring to order the frequent discordant changes of mood and theme in Ernst’s collage– novels, into a logical reading. In as far as Warlick’s alchemical reading of Une Semaine de bonte elucidates the manylayered interpretations of that work, the perspectivism, implied by Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return is equally significant for The Hundred Headless Woman.

A definition of perspectivism is approached by Ernst in his essay Beyond Painting of 1937. He writes: “WHAT IS THE TECHNIQUE OF COLLAGE? If it is plumes that make plumage, it is not glue [colle] that makes gluings [collage] … a hallucinating succession of contradictory images, of double, triple, and multiple images which were superimposed on each other with the persistence and rapidity characteristic of amorous memories … He who says collage, says the irrational.” This important passage is a significant indication of the iconographical structuring of Ernst’s collage–novel. The collage is in fact a collage of ideas, a superimposing of layers of meaning and iconographical references. Decentralising his iconographical structure, Ernst does not maintain a linear relation with his sources. Instead, iconographical motifs are incongrUOUSly dissociated in games of irony, parody, interrogation, innuendo and displacement, continuously dissolving, or at least checkmating, all logical and dialectical structures or stationary identities. In the same sense that the persona of the novel are denied the principle of identity, the basic iconographical structure of the novel functions within a perspectival paradigm. Discussing the contradictory images superimposed in the collage, Ernst indeed claims: “Who knows if we are not somehow preparing ourseives _ to escape from the principle of identity.”

in Nietzsche’s concept of the ’eternal return’, perspectivism is implied by the disorientation of time, seriality, the principle of identity, and determined categories of thought. Reviewing the concept, Pierre Klossowski writes: “Let us suppose that the image of the circle is formed when the soul attains the highest state: something happens to my thought so that … my thought is no longer really my own. Or, perhaps, my thought is so closely identified with this sign that even to invent this sign, this circle, signifies the power of all thought. Does this mean that the thinking subject would lose his own identity? … nothing serves to re–establish the ordinary coherency between self and world as constituted by ordinary usage.”

Ernst’s creation of The Hundred Headless Woman is identified by himself as a process of systematic violence. His view of the creation of the collage–novel closely echoes Nietzsche’s principle of perspectivism and the Dionysian disruption of linear continuance, identities and categories. Denying the principle of identity, Ernst displaces a rational order of the novel by a hallucinating succession of contradictory images. This implies a perspectivism, described by Nietzsche as a decentralisation and disorientation of linear thought. He writes: “Suppose such an incarnate will to contradiction and antinaturalness is induced to philosophize: “upon what will it vent its innermost contrariness? … It will, for example, downgrade physicality to an illusion, likewise … the entire conceptual antithesis subject and object — errors, nothing but errors! To renounce belief in one’s ego, to deny one’s own reality — what a triumph! not merely over the senses, over appearance, but … a violation and cruelty against reason.” Ernst’s interest in the refutation of reason by the irrationality of the collage, his interest in the perspectival approachto Nietzsche’s eternal return, implies, as Nietzsche points out, the downgrading of physicality to an illusion. It also implies an obliteration of a centre of meaning. Considering this violation against reason, Nietzsche claims: “There is only a perspective seeing, only a perspective knowing, and the more affects we allow to speak about one thing, the more complete will our concept of this thing, our objectivity be.”

Pierre Klossowski — philosopher, author, artist, translator of Nietzsche’s Thus spoke Zarathustra and Heidegger’s Nietzsche into French, and also brother of the artist Salthus — has distinguished himself as a major French commentator of Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal return. Since the 1930’s Kiossowski and Georges Bataille were responsible for the formulation of the approach to Nietzsche in Surrealist circles. In the 1960’s when Nietzsche’s work was elevated to the center of the French philosophical stage, Klossowski made an important contribution to the formulation of the deconstructive interpretation of Nietzsche. Bataille’s writings on Nietzsche exerted a fundamental influence on the works of Michel Foucault. Sut the interpretations of Nietzsche by emminent philosophers such as Jacques Derrida, Jean Granier, and Gilles Deleuze look back at the interpretation of Nietzsche in the Surrealist circles since the late 1920’s.

In The Hundred Headless Woman, Max Ernst anticipates many of the concerns, interests and themes in reinterpretation of Nietzsche by recent French philosophers. Ernst’s interpretation of Nietzsche is an example of an outstanding sophistication in the response to Nietzsche in the art arts.